1. Introduction

The fields of Pragmatic Variation and L2 Pragmatics have underscored the importance of recognizing and adapting to different cultural and linguistic norms in an increasingly interconnected world. Pragmatics, roughly defined as language use in context, concerns an individual’s knowledge of what to say (or do) and when. This pragmatic knowledge (and performance) is often associated with appropriate or ‘polite’ behavior (e.g., Locher & Watts, 2005), and as such, has a direct impact on interpersonal relations.[1] This commonsense view of politeness as what is socially appropriate or acceptable is useful for identifying differences in politeness norms as perceived by speakers, and is often referred to as ‘politeness 1’ or ‘first-order politeness,’ (Dimitrova-Galaczi, 2005; Meier, 1995). Given the widespread cross-cultural and cross-linguistic variation in pragmatic norms (i.e., appropriate behavior), L2 pragmatic competence is a core goal of language programs and curricula (Gironzetti & Koike, 2016), and a crucial component of global citizenship. With respect to compliments and compliment responses, it is important for L2 learners to understand when and how to deliver the speech acts (Yousefvand et al., 2014) due to their considerable cross-cultural variation in both form and function (Barros García, 2018), as well as their value as “social lubricants” (Wolfson, 1983, p. 89) and role in indexing solidarity (Haverkate, 2004). In this way, L2 learners may avoid being labeled “insensitive, rude, or inept” for not following appropriate or expected pragmatic routines (Tello Rueda, 2006, p. 169).

Research on Interlanguage and L2 Pragmatics has focused on a variety of factors influencing L2 norm acquisition, two key factors being instructional method and learning context (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig, 2013). Findings have supported the inclusion of explicit pragmatic instruction in language courses, which traditionally have taken more grammar-based approaches that placed less emphasis on cultural or situational contexts (see Gironzetti & Koike, 2016, for an overview of findings and suggestions). Results have also shown the benefits—and limitations—of implicit instruction or exposure to target-like input in the classroom or during immersion experiences, such as study abroad (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig, 2013). Findings regarding the relative effectiveness of implicit and explicit instruction have been varied, and they have shown sensitivity to the specific pragmatic norms or speech acts under study. Among the range of common speech acts, such as requests, refusals, greetings, and leave-takings, compliments and compliment responses remain understudied (Félix‐Brasdefer & Hasler-Barker, 2015; Hasler-Barker, 2016). These two acts can vary pragmalinguistically (i.e., in the linguistic forms used to carry out the acts) from Spanish to English, permitting negative cross-linguistic transfer, and motivating research into enhancing L2 acquisition. The linked acts, studied in tandem, allow unique insights into learners’ abilities to acquire simple formulaic utterances (L2 compliments, which can differ from L1 forms syntactically), in comparison to more varied, sometimes multi-turn utterances (L2 compliment responses, which can differ from L1 norms semantically).

The current study contributes to the debate regarding how to best enhance L2 pragmatic learning by assessing two approaches simultaneously: implicit natural input in a study-abroad environment and explicit instruction in an L2 classroom. It contributes new knowledge of how these different learning environments impact the acquisition of understudied compliments and compliment responses. Furthermore, it sheds light on how the acquisition of two intertwined speech acts proceeds in the two learning contexts, while considering differences in the forms and functions of each act.

In the next section, we provide an overview of research in the field of L2 Pragmatics, with a focus on cross-cultural differences in Spanish and English and the roles of instructional methods and learning environment in L2 pragmatic acquisition. We end the section by presenting our three core research questions. In Section 3, we share the details of the study’s participants, instruments, and methods used in data collection and analysis. We present the results of our study in Section 4, followed by a discussion of our findings in light of existing literature in Section 5. Finally, we present our main conclusions, while acknowledging the study’s limitations and sharing suggestions for future research, in Section 6.

2. Background

2.1. Pragmatics and Pragmatic Variation

Pragmatics is roughly defined as language use in context or ‘meaning in interaction’ (Thomas, 1995). Pragmatic competence can be described in terms of two main components: pragmalinguistic knowledge and sociopragmatic competence (Leech, 1983; Thomas, 1983). The first represents an individual’s access to the appropriate linguistic tools to carry out a given interaction, while the second guides a speaker in deciding which particular linguistic tools are appropriate to use based on the social and interactional context. Because appropriate behavior is often associated with politeness (e.g., Locher & Watts, 2005), pragmatic competence—whether in a first or an additional language—is central to an individual’s performance in forming and maintaining relationships. The linguistic tools and behaviors considered appropriate for a given interaction depend largely on the linguistic and cultural context, as well as the language itself and the speech community in which it is used. This pragmatic variation has been documented across a wide range of languages (cross-linguistic variation) and language varieties (intra-linguistic variation) for a host of different speech acts.

2.2. Pragmatic Variation in Spanish and English Speech Acts

According to Searle (1976), “the basic unit of human linguistic communication is the illocutionary act,” or speech act (p. 1). Common speech acts include greetings, leave-takings, requests, refusals, apologies, compliments, and compliment responses, among others. Although linguistic analysis using speech act theory risks decontextualizing speech from larger conversational and social contexts (see, e.g., Barron, 2003), the framework provides an effective means for cross-linguistic analysis, and measures can be taken to control and account for different contextual variables. Studies of speech acts in Spanish and English have uncovered key similarities and differences, both across the two languages, and across varieties of each language.

Perhaps the most-studied speech act in Spanish and English is the request. Often analyzed in terms of the act’s directness and imposition on the hearer, requests have a fairly transparent tie to politeness perceptions. Folk notions of politeness, referred to as ‘politeness 1’ or ‘first-order politeness,’ are useful for identifying differences in politeness norms as perceived by speakers, as they represent a commonsense view of politeness as what is socially appropriate or acceptable (Dimitrova-Galaczi, 2005; Meier, 1995). A direct request employing a command form, such as “Give me a coffee” can be perceived as placing a different level of imposition on the recipient than a request such as “Can I have a coffee, please?” The latter utilizes a question to deliver the request, along with several additional mitigators: modal ‘Can’, the softener ‘please’, and a speaker-centered (can I have) versus hearer-centered ([you] give) structure. The conventions regarding use of more-direct versus less-direct requests, along with use of mitigators, vary largely by language and culture. Although speakers may not be conscious of the typical routines and formulas they use to make speech acts, such as requests, they often have intuitions regarding which forms are appropriate in a given context, which they may describe in terms of politeness.

Cross-linguistic differences between Spanish and English request strategies have direct bearing on politeness perceptions. Across varieties of Spanish, direct, less-mitigated request strategies, such as Dame un café (‘Give me a coffee’), abound, although there is notable intra-linguistic variation across varieties of Spanish (e.g., Félix-Brasdefer, 2009; Márquez Reiter, 2002; Placencia, 2008). Aside from regional variation, there may also be variation according to social factors, such as gender (Félix-Brasdefer, 2012; Michno, 2019; Yates, 2015). In English, on the other hand, the conventionally indirect request (“Can I have a coffee, please?”), a strategy that is absent in Spanish, dominates in frequency.

Strategies for a range of speech acts can be tied to politeness or described as being appropriate or inappropriate to some degree. While, at times, a particular strategy may be perceived simply as ‘foreign,’ due to common negative cross-linguistic transfer (e.g., conventionally-indirect requests transferred to L2 Spanish by L1 English speakers), other strategies, such as unmitigated requests in English (by an L1 Spanish speaker, for example) might be described as ‘impolite’ or ‘rude,’ having potentially detrimental impact to interpersonal relations (and perceptions of others), even during fleeting daily interactions.

Refusal strategies, for example, can carry similar politeness-related weight, but in the opposite direction with respect to directness. A brief description of involvement- versus independence-face systems is helpful in understanding the distinction. According to Scollon and Scollon (2001), certain cultures tend to orient toward indexing involvement, or solidarity, among interlocutors, while others orient toward their independence, or freedom from imposition. This builds upon Brown and Levinson’s (1987) descriptions of positive and negative face and face systems. In a cultural context where an involvement-orientation is expected, a refusal to an invitation, for example, might entail language and/or behaviors to mitigate the threat to solidarity inherent in denying the hearer’s invitation. In an independence-oriented context, on the other hand, an appropriate refusal might be more direct or unmitigated. Such differences in face orientation exist both within and across languages. Félix-Brasdefer (2008), for example, found intralinguistic pragmatic variation in refusals between Mexican and Dominican Spanish, with Mexican Spanish speakers using more indirect and mitigated strategies. Notably, the author identified the importance of considering social distance (familiarity) between interlocutors. He found that, among Mexican Spanish speakers, refusal strategies differed for well-known interlocutors versus strangers. In the L2 realm, Félix-Brasdefer (2013) found that L1 English learners of Spanish diverged from native speaker norms for refusals; this was true for students in a traditional classroom and in a study-abroad environment. Study of requests and refusals together can help researchers and language learners to understand the intricacies of face systems and how expected orientation to involvement or independence face can vary from moment to moment. The two acts form an adjacency pair, with requests forming a first pair part on which the refusal depends. An L2 Spanish learner must realize that different involvement strategies are appropriate for making a request (i.e., more direct), and in the immediately following conversational turn, a refusal (less direct, mitigated).

Similar pragmatic variation has been observed while comparing greeting and leave-taking behavior in Spanish and English and across varieties of Spanish (e.g., Pinto, 2008; Placencia, 1997), with notable challenges for speakers in bilingual communities, where two sets of ‘appropriate’ strategies may be perceived depending on the sociolinguistic context (Michno, 2017). With these two particular speech acts, not only the form of the act, but the expectation of receiving the act, can vary across languages and cultures (Michno, 2017). Greetings and leave-takings in Spanish, for example, might be culturally expected in instances where they are viewed as optional or unnecessary in English. Spanish-English bilinguals have noted different expectations according to language in group settings: in Spanish, individual greetings and leave-takings are expected, while in English, it is acceptable to address the group as a whole or even omit the acts (Michno, 2017). Additionally, the acts can be modified to enhance solidarity, through personalization (i.e., use of addressees’ names or specific details related to them as individuals), the use of excuses to mitigate leave-taking, and other strategies, according to cultural norms. Greetings and leave-takings are similar to compliments and compliment responses in their largely interpersonal function. As expressive speech acts, they provide windows into the minds of speakers and allow them to take stances with their interlocutors (Searle, 1976). The acts are often studied in tandem to allow researchers to understand how in-group members index solidarity and/or independence when coming into contact with one another. This knowledge helps to address potential transfer of L1 norms by L2 learners that might clash with target-culture expectations. While greetings and leave-takings are not connected in a conversational structural sense (i.e., they typically involve separate sequences and do not form an adjacency pair), they are similar to compliments and compliment responses in terms of their interpersonal functions and association with appropriate behavior (i.e., folk notions of politeness).

2.3. Compliment and Compliment Response Strategies in Spanish and English

Compliments and compliment responses fall under the category of expressive speech acts (Searle, 1976) and, as such, serve to represent the psychological state of the speaker. Both speech acts have clear social value, as they are used to index solidarity (Haverkate, 2004) and can play a key function in opening or continuing interactions (Wolfson, 1983). Indeed, they have been described as “social lubricants” (Wolfson, 1983, p. 89). Hasler-Barker (2016) observes that “compliments and compliment responses are strikingly formulaic, comprising only a few syntactic (compliments) or semantic (compliment responses) formulas” (p.127). Because the two acts are intertwined (i.e., they form an adjacency pair), it is helpful to consider them together in order to understand the way they interact (Hasler-Barker, 2016). Compliments and compliment responses are used on a daily basis in order to create and maintain relationships among a variety of people.

There are a number of distinct strategies when it comes to producing both compliments and compliment responses in English and Spanish. The literature identifies two very common compliment constructions as ‘Qadj’ or ‘How [adj]’ (e.g., Qué rica tu paella ‘How delicious, your paella’), a construction favored by native Spanish speakers, and ‘megustaN’ or ‘I like [N]’ (e.g., Me gusta la casa ‘I like the house’), favored by native English speakers (Hasler-Barker, 2016). Typical compliment response strategies in English include self-praise, or appreciation, while in Spanish, the more common compliment response strategies are expansion or seeking confirmation, both forms of fishing for either more information or more compliments (Hasler-Barker, 2016). Additionally, Smith (2009) states that native English speakers return compliments more often than native Spanish speakers and generally give compliments more frequently and for a broader variety of reasons. English speakers also frequently tend to accept compliments with the ‘appreciat’ strategy (saying ‘thank you’) and end the compliment-compliment response exchange there, while there may be more turn-taking with Spanish speakers, as compliments occur less often (Smith, 2009). Mir and Cots (2017) find that because compliments are more common in English conversations, there is a higher frequency of compliments to respond to in American English. Therefore, compliment responses may be very formulaic, as opposed to the wider variety of compliment response strategies in Spanish, which are used less often. The common response of ‘thank you’ in English is acceptable in most contexts, and therefore, many English speakers may simply transfer this English fixed expression to Spanish, responding to a wide variety of compliments with a simple gracias. In addition, L2 learners of Spanish are commonly taught the compliment construction me gusta (‘I like’), which mirrors L1 English norms, leading many speakers to frequently produce this strategy, despite its infrequent use among native speakers of Spanish (Hasler-Barker, 2016).

2.4. L2 pragmatics and Speech Acts

In the realm of L2 pragmatics, increasing attention has been given to enhancing L2 acquisition of pragmatic norms, including in the delivery of different speech acts (Bataller, 2010; Cohen & Shively, 2007). Studies have uncovered the effects of multiple factors influencing pragmatic learning, some tied to the type of input learners receive, and others tied to the learners themselves (e.g., proficiency, motivation, intensity of interaction with the language (Bardovi-Harlig & Bastos, 2011). A key factor to emerge is the context of learning (e.g., classroom versus study-abroad), described as one of the most important variables in SLA more broadly (Collentine, 2009), which can be intertwined with explicit and implicit learning.

Researchers have recognized the value in assessing the effectiveness of L2 pragmatic norm acquisition in the study abroad context, in particular (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig & Bastos, 2011; Félix-Brasdefer, 2004; Félix‐Brasdefer & Hasler-Barker, 2015). While studies have identified some positive impacts of the SA environment, they have also suggested a limited effect of SA language immersion programs on the acquisition of pragmatic norms due to lack of sufficient input (Barron, 2003; Bataller, 2010) or corrective feedback from target-language speakers. Some scholars suggest that semester- or even year-long programs may be too short for pragmatic changes (e.g., Bataller, 2010), although others claim that intensity of interaction with host country residents is more important than length of stay (Bardovi-Harlig & Bastos, 2011; Felix-Brasdefer, 2013). Intensity of interaction has been operationalized using a variety of metrics, typically self-reported, that capture the amount and types of interaction program participants have with locals on a daily and weekly basis. Recent studies have begun to assess L2 acquisition during short-term SA programs (variably defined as less than three months [Allen, 2010] or two months or less [Martinsen, 2008]), testing the claim that program duration, in and of itself, has bearing on learning outcomes. Results from these studies have also been mixed, but they have shown the possibility of some pragmatic learning in the short term, suggesting that types and amount of input matter more than length of stay (e.g., Czerwionka & Cuza, 2017; DiBartolomeo et al., 2019; Félix‐Brasdefer & Hasler-Barker, 2015). These findings support the broader view in SLA that it is important to consider the types and qualities of input (see, e.g., Segalowitz et al., 2005), as well as Schmidt’s (2010) Noticing Hypothesis, which suggests that pragmatic features in the input must be attended to consciously in order for input to become intake and for learning to occur. This view explains the benefits of explicit instruction in facilitating learner awareness (e.g., Cohen & Shively, 2007). The Noticing Hypothesis motivates the use of awareness-raising activities, broadly speaking, to help students notice and attend to specific pragmatic features and cultural practices, in the hopes of enhancing student understanding and adoption of target norms. The disparity in findings of L2 pragmatic learning in the SA context suggests a need for additional pedagogical intervention, and for more research into what particular aspects of L2 pragmatic acquisition benefit from explicit intervention versus implicit input. Some research has begun to explore this realm: Hernández & Boero (2018), for example, found that brief explicit instruction on Spanish requests prior to a short-term SA program improved participant request performance. More research combining SA and pedagogical intervention is much needed.

In terms of pedagogical interventions, researchers and educators have utilized a variety of methods to enhance L2 pragmatic learning, including role plays, exposure to authentic data, cross-cultural analysis, form-focused instruction, and guided practice (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig & Mahan-Taylor, 2003; Ishihara & Cohen, 2010; Tatsuki & Houck, 2010). Findings suggest that, in general, instruction is beneficial, although explicit instruction may carry more benefits than implicit instruction or input (Rose & Kasper, 2001). With respect to L2 Spanish compliments and compliment responses, in particular, Hasler-Barker (2016) provides a detailed account of the impacts of multiple interventions in the classroom context. The researcher found modest improvements among two groups of intermediate-level learners receiving explicit or implicit pragmatics instruction. Namely, students in both groups decreased use of the non-target compliment strategy ‘megustaN’ (‘I like [noun]’), although they did not increase production of the intended target: ‘Qadj’ (‘how[adj]’). Notably, only members of the explicit instruction group maintained the reduction of the non-target form in a delayed post-test, suggesting a benefit of explicit learning techniques. For compliment responses, both groups showed some movement toward target strategies (an increase in self-praise), but neither employed the target strategy of fishing. In sum, the researcher found some small benefits for both implicit and explicit instruction, but, unable to gauge their relative merits, recommended combining the two to maximize learning outcomes.

There remains a need to assess the relative effects of different learning contexts (study-abroad versus the at-home classroom) on the acquisition of L2 pragmatics in a controlled fashion, particularly among understudied speech acts, such as compliments. While there have been limited analyses of the effect of classroom instruction or the effect of study-abroad on L2 Spanish compliment acquisition, simultaneous analyses of the two contexts using comparable assessment tools and participant groups is lacking. The present study fills that gap. It also heeds Hasler-Barker’s (2016) call to consider compliments and compliment responses in tandem to better understand their interconnectedness, while it also specifically considers how L2 acquisition proceeds in light of the similarities and differences between the two speech acts.

The present study seeks to examine the following three research questions:

-

Will exposure to target-language (Spanish) speakers during a semester-long study abroad lead to production of more target-like L2 Spanish compliments and compliment responses?

-

Will explicit instruction at the home institution produce compliments and compliment responses that tend towards target language norms? How does learning compare to the SA environment?

-

Are compliment and compliment response strategies conditioned by the perceived social distance (+D/-D) between speaker and addressee?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Thirty-six undergraduate students (aged 19-22) participated in this study, all of them completing upper-level coursework for a Spanish major at the same liberal arts university in the Southeastern US. Participants comprised three different groups: 16 participants in a study abroad (SA) group in Madrid, Spain; 15 in a classroom instruction (CI) group, receiving explicit instruction on L2 Spanish speech acts on the home campus; and an additional 5 students serving as an at-home (AH) language class comparison group, also residing on the home campus. We opted to include a small at-home comparison group based on observations that some type of comparison group is better than none (Solon & Long, 2018, in reference to studies of SA phonetics and phonology). While, based on methodologies and results from relevant L2 pragmatics research, we consider the baseline data for the SA and CI groups sufficient for addressing our specific research questions, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the small comparison group size and results should be interpreted with caution.[2] The AH control group was enrolled in the same class as the SA group (Advanced Spanish Oral and Written Expression) during the study period; neither the AH nor the SA group received explicit instruction on L2 Spanish speech acts as part of the study. In an effort to enhance the input and noticing of authentic Spanish language for SA and AH participants, the course instructors required students to take ethnographic field notes of Spanish language use in public spaces, which served as content for class discussions and written reflections (see Michno & Lozano-Alonso, 2024). The instruction for the CI group included a two-week unit on speech acts in Spanish, with cross-cultural comparisons to English. Students were provided with authentic speech act usage in context, they participated in role-plays using authentic dialogues, and they engaged in metapragmatic discussion of cross-cultural differences of speech acts. SA participants spent four months in Madrid, living with host families and taking classes with Spanish professors four days a week. All participants were assessed as falling within the intermediate-mid to advanced-low proficiency range according to ACTFL guidelines via Oral Proficiency Interviews conducted by a faculty member at the home institution.

3.2. Elicitation Procedures

To gather data for this study, a modified oral Discourse Completion Task (DCT) was used in a pre-/post-test design to elicit 10 different speech act types from participants. The task was administered to participants at two different time points: the first week and the last (14th) week of the semester. DCTs can be effective tools for gathering naturalistic speech act data in a structured experimental format. Although they may not allow access to truly naturally occurring speech act production (Cohen, 2013; Golato, 2003), they can approximate natural speech production and have the benefit of maximizing comparable data across participants and participant groups. Furthermore, elicited productions can be more useful than natural speech (Schneider, 2012), by allowing “access to (metapragmatic) perceptions about appropriate behavior” (Placencia, 2011, p. 100).

The modified DCT utilized in this study was informed by Hasler-Barker (2013) and Félix-Brasdefer and Hasler-Barker (2015), who enhanced traditional DCT design through several modifications. The version utilized in the present study benefits from the inclusion of images, time-limited participant response windows, and oral (versus written) participant responses. The images served to control the participants’ frames of reference (see, e.g., Bednarek, 2005; Koike, 2012) with respect to the interactional partner(s) and context of each elicited speech act. The time-constraint simulated real-world interactions by requiring participants to respond to the 28 different conversational prompts in the moment, without extended time for planning or editing, allowing insights into participants’ pragmatic knowledge (Cohen, 2013). The DCT was administered using a PowerPoint presentation, which was automated to advance from one speech act prompt to the next in a fixed order, allowing participants 20-second windows to verbally respond to each prompt. The fixed presentation order ensured that participants were not primed by DCT-delivered speech acts prior to producing the speech acts themselves. Because several of the speech acts belonged to adjacency pairs, it was imperative that participants were prompted to produce a first pair part (e.g., a request or a compliment) before encountering a DCT-generated request or compliment that served to prompt a second pair part (e.g., a refusal or a compliment response). The prompts designed to elicit compliments and compliment responses included: complimenting a strangers’ shoes, complimenting a host mother’s cooking (paella), responding to a stranger’s compliment regarding clothing, and responding to a host mother’s compliment about Spanish language use.[3] These acts, as with all acts in the DCT, were balanced for social distance, with one situation involving a close acquaintance (-D) and another involving a stranger (+D). All acts were controlled for social power, involving -P interactions. Participants completed the DCT independently using a personal computer while audio-recording their responses. These audio recordings were submitted to the research team and subsequently transcribed and categorized by speech act, allowing for the coding of each individual speech act by strategy type.

3.3. Data Coding and Analysis

Each speech act was coded according to the type and number of strategies used. The lists of strategies were unique to each act. The list of strategies used to code compliments (Table 1) was informed by previous research (Félix‐Brasdefer & Hasler-Barker, 2015; Hasler-Barker, 2013; Nelson & Hall, 1999; Placencia & Yepez, 1999; Wolfson, 1983).

The compliment strategy types are described through both parts of speech, such as nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc., as well as through common terms in Spanish, like me gusta ‘I like’, es muy… ‘it’s very…’, or te queda ‘it suits/fits you’. It is useful to combine both types of description in order to best represent how speakers will produce a variety of different compliments. The last strategy type is an adjective combined with an intensifier like muy ‘very’ or bastante ‘rather’. An example of each strategy type is given for clarity, with its English translation.

Like the compliments, the compliment responses were also coded according to the type and number of strategies used. Strategy types, shown in Table 2 alongside examples and English translations, were again informed by previous research (Hasler-Barker, 2016; Mir & Cots, 2017; Munawwaroh & Ishlahiyah, 2021; Smith, 2009).

The compliment response strategies were different from compliment strategies, as they are described by different functions, rather than parts of speech and formulaic phrases. These strategies can be used by themselves, or in conjunction with each other. For example, many compliment responses included both a token of appreciation as well as an additional comment. While some of the strategies may seem similar, there are distinct differences. The word ‘too’ is necessary to categorize a response as using the accept strategy, while a token of appreciation is any variation of the phrase ‘thank you.’ A comment simply provides more information regarding the compliment, while an expansion aims to continue the conversation surrounding the compliment. Examples of each type of strategy are given for clarity, and a direct English translation is also provided.

Once compliments and compliment responses were coded according to strategy, they were designated as native-like or non-native-like according to descriptions in the literature. Both researchers reviewed all coding to ensure inter-coder reliability. Finally, in addition to coding for compliment and compliment response strategies, the adjectives used within compliments were identified to search for patterns within and across the groups over time. This served to gauge growth in vocabulary and adoption of regional or colloquial forms over time. Descriptive statistics were calculated using Microsoft Excel to compare pre-/post-session use of each speech act according to strategy type in terms of raw counts and percentages. Mixed-effects logistic regression analysis was carried out in R (R Core Team, 2023) to assess significance of group-wise patterns while also considering the impact of social distance on strategy use over time.

4. Results

4.1. Compliments

Overall, for both the SA and CI groups, there was an increase from the pre- to post-test in the number of native-like strategies produced (‘Qadj’ or ‘how[adj]’), and a corresponding decrease in the non-native-like strategies produced (‘megustaN’ or ‘I like [noun]’). The CI group saw a significant increase in the number of tokens of ‘Qadj,’ from 4 (17%) to 12 (50%), and corresponding decrease of ‘megustaN,’ from 19 (83%) to 12 (50%). Results were even more pronounced for the SA group, as shown clearly in Figure 1 in the increased production of the ‘Qadj’ strategy type, from 2 (7%) in the pre-test to 16 (52%) in the post-test. The AH group, however, saw very little change with just one token of ‘Qadj’ in both the pre- and post-test, and there was even a slight increase, from 5 to 7, in the use of the ‘megustaN’ strategy type.

Mixed-effects logistic regression analysis of compliment production, including participant as a random factor, showed an effect for session on the SA and CI groups’ compliment production: Both groups significantly increased target compliment strategy use over time (Table 3).[4] An effect was also revealed for familiarity with the interlocutor as an interpersonal variable. Participants were more likely to use target forms with familiar acquaintances. This pattern in the data suggests that participants may be sensitive to interpersonal dynamics to the degree that it impacts selection of compliment forms.

Further analysis of SA participants was conducted to assess the types of relevant input they may have encountered during the semester. Participant data revealed that half (eight) of the students acquired explicit awareness of the target compliment strategy ‘Qadj’ (‘How [adj]’) and how it differed from English. This awareness likely contributed to the SA group’s overall increase in target form usage. Six of these eight students were the only students to use the target form with the DCT stranger prompt (complimenting a stranger’s shoes)—and they did so only at the end of the semester, suggesting a change in their awareness of and willingness to use the new strategy.

In addition to strategy type, compliments were analyzed for adjective use. Table 4 gives an overview of the adjectives used within the compliments produced by all participants pre- and post-semester.

While the overall number of adjectives used in compliments increased from 49 pre-semester to 61 post-semester, across all participants, the number of unique adjectives stayed the same: 14. Nonetheless, use of adjectives regionally associated with Spain (guay, molas) only appeared in the post session and primarily came from the SA group. The two tokens of guay in the CI group might have resulted from contact with students who had previously studied in Spain or through other uncontrolled inputs (other classes, acquaintances, media, etc.). Additionally, many of the adjective choices were likely influenced by the situations presented in the DCT. This is especially evident with the adjective rico ‘delicious.’ There were 16 tokens of the adjective rico in the context of complimenting a host mother’s dinner.

4.2. Compliment Responses

The Spanish native-like strategies for compliment responses, ‘agreement’ and ‘fishing,’ were not produced by any participants in the dataset in either the pre- or post-session. Instead, the most frequently-used strategies were ‘appreciat,’ (showing appreciation, saying ‘thank you,’) as well as ‘comment,’ (providing additional commentary regarding the compliment, such as where the item being complimented was from).

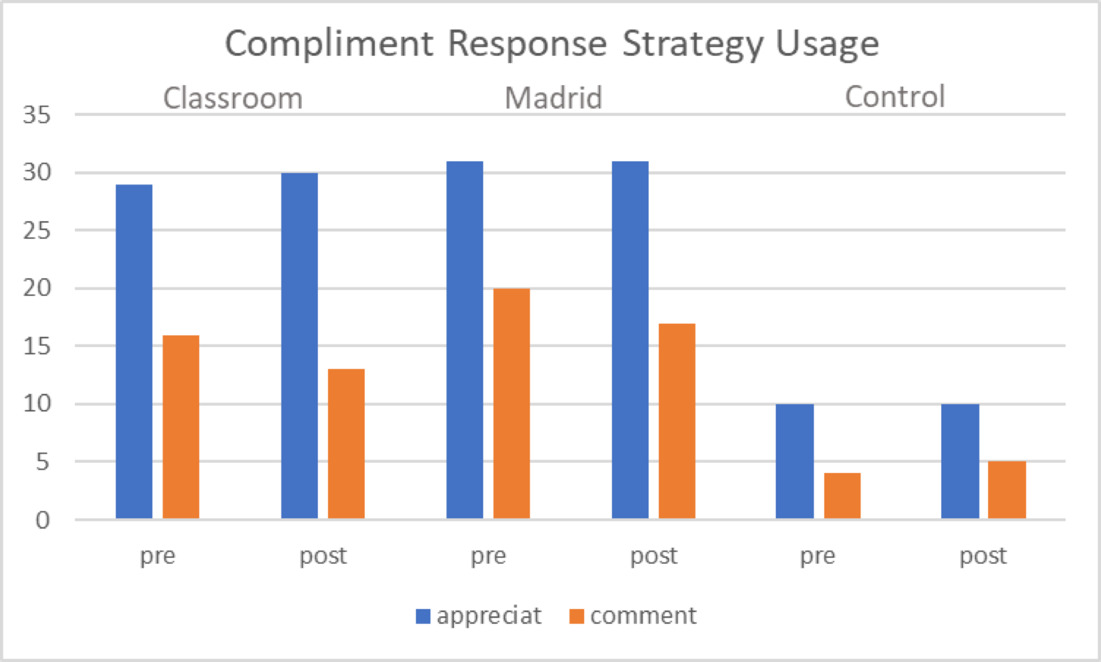

These non-native-like strategies were produced in almost the same manner on the pre- and post-tests. The ‘appreciat’ strategy was produced the same number of times in pre- and post-tests for both the SA group (31 times) and the AH group (10 times), with minimal increase for the CI group, from 29 to 30 tokens. The results were similar for the production of the ‘comment’ strategy. The number of productions of the ‘comment’ strategy decreased slightly in both the SA group (from 20 to 17 tokens) and the CI group (from 16 to 13 tokens), while there was a slight increase from 4 to 5 tokens in the AH group. Figure 2 demonstrates the almost identical results from each participant group.

5. Discussion

Compliment production at the beginning of the semester by all three groups in this study aligned with patterns described in the literature for L1 English speakers. The most frequent compliment type was ‘megustaN’ or ‘I like [noun]’, accounting for 88% (50/57) of all compliment types. Results show, however, that both the study-abroad and the classroom instruction contexts were effective in increasing use of the target L2 Spanish form (‘Qadj’ or ‘how[adj]’), with percentages rising to around 50% for these two groups, in comparison to the control group, which showed no substantial change by the end of the semester. These findings suggest that both learning contexts—study-abroad and explicit classroom instruction—were effective in enhancing acquisition of L2 Spanish compliments. Furthermore, the similarity between the two groups, in terms of target production frequency, suggests that the contexts are similarly effective in this specific regard. This finding seems to corroborate Félix-Brasdefer & Hasler-Barker’s (2015) findings in the SA context, which showed a modest increase in target compliment production (‘Qadj’ or ‘how[adj]’) over the course of a shorter, eight-week, study-abroad program; although the production of non-target ‘megustaN’ (‘I like [noun]’) persisted in the post-test well beyond native-speaker norms. The findings of the present study conflict, however, with those of Hasler-Barker (2016) in the classroom instruction setting: Hasler-Barker’s study showed no impact of instruction—explicit or implicit—on the production of target compliment ‘Qadj’ or (‘how[adj]’). That study did report, however, a decrease in the use of non-target ‘megustaN’ (‘I like [noun]’). The discrepancy with the present study’s findings could be tied to the specific instructional methods utilized. Participants in Hasler-Barker’s (2016) study received 40 minutes of instruction on compliments and compliment responses in a language class taught by a non-linguist, followed by ten minutes of role play, whereas the current study’s CI group received a multi-week unit on speech acts in Spanish and English, as part of a class on pragmatics and pragmatic variation. Indeed, Gómez and Ede-Hernandez (2021) remark on the value of providing students with more contact hours and a variety of instructional methods to increase target compliment and compliment response performance, even among students who have already completed a study abroad program.

Importantly, the present study provides evidence that both SA and CI contexts can be comparably effective by using the same controlled methodology to assess participant learning in both environments, while also comparing them to a small group of similar at-home peers enrolled in a language class without pragmatics instruction. For this simple, conventionalized compliment formula, at least, it seems that implicit input and explicit instruction are on relatively equal footing, in the immediate term, at least. Of course, this assertion is specific to the semester study-abroad context, which may offer more (or more sustained) input than implicit instruction methods in the classroom (e.g., Hasler-Barker, 2016). Additionally, SA participant data revealed the wide variety of types of input, both explicit and implicit, that learners encounter in the everyday SA environment. Half of the students, for example, gained metalinguistic awareness of the target compliment strategy during their semester abroad. These students were more likely to use the target formula in the post-semester DCT prompt eliciting a compliment to a stranger. This finding aligns with Segalowitz et al.‘s (2005) remarks on the value of focusing learners’ attention on relevant language, whether it be through planned instruction or impromptu means that can occur at any time during a study-abroad experience: in the classroom, with a host family or local friends, or in everyday public settings. It supports the view that students must become aware of and willing to use target pragmatic forms and routines (Xiao, 2015), and that some type of awareness-raising—beyond traditional language classroom exposure—is necessary, or at least advantageous, for increasing target pragmatic performance (Félix‐Brasdefer & Hasler-Barker, 2015).

It may prove fruitful to further assess participant acquisition using a delayed post-test similar to Hasler-Barker (2016), for example, to determine if one context or the other (SA or CI) better engenders sustained target language use. With respect to situational social factors, the study suggests that participants were sensitive to social distance to the extent that it significantly affected their compliment strategy use (eliciting more ‘megustaN’ or ‘I like [noun]’ structures with strangers). This pattern, which also extended to both SA and CI groups, mirrors findings by Félix-Brasdefer (2008) of refusals in Mexican Spanish, which differed in directness according to social distance. Perhaps it was the perceived orientation to involvement- versus independence-face systems that guided participants in their varied compliment use with a close acquaintance and a stranger. Or perhaps it was something tied to the compliment itself or to the imagined frame (Bednarek, 2005; Koike, 2012). To further investigate this line of inquiry, more DCT situations should be provided to the participants that, crucially, hold other factors constant while varying the interpersonal familiarity variable. The present study’s design risks conflating interpersonal dynamics with other situational variables, such as the social and discourse contexts of the compliment being elicited. The compliment to the stranger, for example, served as a conversational opening, whereas the compliment to the host mother was likely imagined in the context of ongoing discourse, depending on the participants’ frames of reference. Nonetheless, these findings support a complex view of L2 pragmatic acquisition that moves beyond simple use/non-use of target forms over time and is instead sensitive to overlapping linguistic and extralinguistic situational variables.

In the context of compliment responses, on the other hand, no notable differences surfaced among the three groups, nor was there observable change from pre- to post-semester. This finding suggests that, despite explicit instruction regarding native-speaker expectations and routines (CI group), or exposure to natural input in the target language environment (SA group), the forms and routines for realizing compliment responses were not acquired by participants to the degree that they were elicited by oral DCT prompts. This echoes findings of L2 Spanish learners in SA and classroom contexts for refusals (Félix-Brasdefer, 2008). In this light, the study supports the view that there are likely other factors at play, and that (at least certain types of) explicit instruction or SA implicit input are not sufficient, in and of themselves, to effect movement toward target performance among intermediate-mid to advanced-low L2 learners.

The absence of target-like performance with compliment responses could be due to multiple, perhaps overlapping, factors. For one, SA participants simply may have not encountered sufficient input (i.e., compliment responses in natural interactions) during their time abroad. Secondly, they may not have noticed the acts or attended to them in a way that allowed discovery of cross-linguistic differences (Schmidt, 2010; Segalowitz et al., 2005). As observed in the literature, pragmatic norm acquisition can be limited during study-abroad language immersion programs due to lack of sufficient input or corrective feedback from target-language speakers (Barron, 2003; Bataller, 2010). Schmidt (2010) emphasizes that care must be taken to focus learners’ attention on relevant input to encourage noticing, including in the SA context (Segalowitz et al., 2005). The study-abroad participants may not have focused on these particular speech acts, which occur less frequently than ubiquitous requests, for example.

What’s more, some target compliment responses in Spanish (e.g., fishing) may be associated with additional conversational turns, something not possible with the DCT. This may encourage participants, perhaps subconsciously, to opt for short and simple appreciation responses instead, such as ‘thanks’ (see Koike, 1989). The semantic and pragmatic subtleties of compliment-compliment response discourse may be lost on SA participants (or L2 learners, more generally), who, depending on their language proficiency, may be attending to other aspects of meaning-making in interaction. They may, for example, be more focused on lexical items or syntactic constructions (or simply on gaining the information they seek in the broader interaction). As the compliment-compliment response sequence serves a primarily interpersonal function (of which participants are likely unaware, consciously, at least), the finer points (and discourse norms) may escape their attention as they manage their cognitive loads in real time. Nonetheless, Hasler-Barker (2016) did see some minor movement toward native Spanish compliment responses by learners receiving both implicit and explicit metapragmatic instruction. That study’s methodology, however, engaged participants in role plays, which promoted more naturalistic speech with plenty of opportunity for feedback and turn-taking. Thus, the assessment tool as well as the instructional method must be carefully considered when interpreting results. Future research might include some combination of assessment mechanisms to better triangulate pragmatic knowledge and performance.

These findings have several pedagogical implications. First, they suggest that short formulaic speech acts, such as compliments, can be acquired with a high degree of success through both implicit and explicit means. This appears to be true even for acts that differ substantially from the L1, either in form or frequency (e.g., ‘Qadj’ or ‘how[adj]’). SA participants were able to acquire and significantly increase use of this target form on par with CI students who received explicit instruction and practice. In this light, educators might focus more on the discourse and cultural dynamics that condition more complex, potentially multi-turn acts, such as compliment responses. Perhaps through additional metapragmatic instruction and practice—instructors can raise learners’ awareness of pragmalinguistic resources beyond words and phrases to discourse-level patterns. Discussion of not only what to say, but when to say it and how much to say, could concurrently increase learners’ sociopragmatic competence and their attention to cross-cultural variation in face wants and associated perceptions of politeness.

6. Conclusions

This study has shown clear benefits for both the study abroad and explicit classroom instruction contexts on L2 learner production of native-like Spanish compliment strategies. The same cannot be said, however, for compliment responses: native-like strategies were completely absent among all three participant groups both pre- and post-semester. This may very well be an artifact of the DCT methodology, which does not encourage multi-turn acts, including compliment-compliment response sequences typical in L1 Spanish. Similarly, any notions of face, politeness, or other interpersonal nuances may have been lost on (or at least diminished among) study participants, who were only imagining an interaction with another person. They were unable to create compliment response turns that prompted a following turn by their interlocutor, as corresponds to the target ‘fishing’ strategy.

In addition to these methodological limitations, the study might also benefit from a larger comparison group (present study, n = 5), as well as groups receiving different types and amounts of explicit and implicit instruction, to better tease apart the specific inputs and instructional methods benefiting formulaic versus discourse-level target performance. Finally, researchers might also choose to expand the situations examined, whether through DCT or other means, to assess the interplay of situational (compliment types), interpersonal (e.g., along power and solidarity axes), and other extralinguistic variables (e.g., proficiency, motivation, intensity of interaction).