1. Introduction

Intonation studies have been increasing during this century. Technological advances in recording apps, a well-established framework, and a simplified tool to name intonation contours have helped the description of diverse dialects in Spanish. However, despite the advances, the progress is slow. Every study contributes a limited quantity of data due to the manual analysis required by the researchers. Thus, the findings shared here contribute to the understanding of intonation patterns in a specific dialectal area in Colombia and promote new discussions regarding the interface between prosody and syntax.

This project aims at answering the questions: What are the intonation patterns in the Spanish spoken in Pasto? Are there intonation strategies to differentiate new vs old information? The research aims to explore broad-focus and narrow-focus sentences emphasizing the subject and the object in the Spanish spoken in Pasto and find the intonation strategies to organize information orally.

Intonation, characterized by pitch, stress, and rhythm variations, plays a pivotal role in conveying meaning and structuring communication in spoken language. Similarly, focus marking involves highlighting specific elements within a sentence to draw attention to new or valuable information. By examining how these two phenomena intersect and influence each other, we aim to deepen our understanding of language structure in one of the many Andean varieties of Spanish.

The order of the article is as follows. First, we briefly review the evolution of Colombian intonation and the study of intonation and focus on Spanish. The second part, we describe the methodology, including information about participants, materials, and data analysis. Third, we share the preliminary results organized by type of focus: broad focus sentences first, followed by narrow focus on the subject and the third section is for the narrow focus on the object. Each section contains a sample sentence and bar charts with the pitch accent frequency. In the fourth section we discuss the most common contours found in the subject, verb, and object, with an acknowledgement of the limitations of this study. Lastly, in conclusion, we share the insights and future research recommendations to contribute to the understanding of prosody and focus marking.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intonation in Colombia

Research of intonation in Colombia has covered main cities like Bogotá and Medellín. However, research on decentralized cities is scarce. The first reports about Colombian intonation are based on general adjectives such as Strong, elongated, soft, that acknowledge diverse melodies depending on the dialect (Cuervo, 1954; Eastman, 1926; Flórez, 1951, 1957, 1965; López de Mesa, 1934). However, this situation rapidly evolves as empirical descriptions of intonation worldwide are developing. Among the most promising ones is Pierrehumbert’s AutoSegmental Metrical (AM) Model (1980). This proposal sets the framework to identify the melody of the voice as part of the suprasegmental realm, where pitch and boundary tones correlate to the stress in the words within a sentence. These pitch movements are a combination of high (H) and low (L) tones that we identify and annotate by observing the fundamental frequency (from now on, F0) in software programs like Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2024).

The methodology provided by this framework allowed Sosa (1999) to describe the intonation of several Hispanic countries and sets the scene for the proliferation of studies in the 21st century. In his study, Sosa explored and identified intonation patterns that provided a first catalog with the potential of becoming the starting point to understanding intonation associated with dialectal variation.

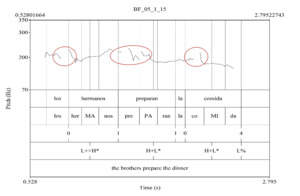

To continue the exploration of diverse intonation patterns, it became clear that a consistent set of contours would ensure the description of such melodies around the Hispanic world. This set became the Spanish Tones and Break Indices (Sp_ToBI), a label system that describes the contours of the voice’s F0 in the Spanish language (Prieto Vives, 2005) with subsequent revisions (Estebas Vilaplana & Prieto Vives, 2008; Hualde & Prieto Vives, 2016). This system provides an inventory of high (H) and low (L) pitch accent combinations. Researchers all over the world have access to this system by visiting the website https://sp-tobi.upf.edu/ (Aguilar et al., 2024). It offers training on the labels and contains the contours reported in Spanish studies (Prieto & Roseano, 2010). The webpage provides a description of the prosodic phrasing and tonal representations, visual aids and audio samples as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 shows the pitch accents with visual aids. They are on the top menu, which says Pitch accents selector. They work as an abstraction where a box shows three sections. The dark section in the middle represents an accented syllable, and the adjacent lighter sections represent unstressed syllables. The horizontal line indicates the F0 contour. This screenshot shows the label (L+H*) displayed with the abstract box, a description, an audio sample, and a spectrogram. The prosodic boundaries option in the menu on the left provides numbers to label words (1) and intermediate phrasing (3) of intonational phrases (4). These labels contribute to standardizing the description of the pitch accents present in a sentence.

Current studies on intonation rely on this label system as it facilitates the process of tagging the movements of the melody of the Spanish language. This standard annotation also permits the comparison between intonational studies that use the same system and the enrichment of the database of typical contours found in the Spanish language.

In Colombia, Sp_ToBI has facilitated the description of the Spanish spoken in Medellín (M. A. Muñetón Ayala, 2016; M. Muñetón Ayala & Dorta Luis, 2015, 2017; Muñoz-Builes, 2013, 2020, 2021; Osorio & Muñoz-Builes, 2011; Vásquez et al., 2020; Velásquez-Upegui, 2013). In general, Medellín Spanish portrays a standard configuration L+H* L% for broad focus, while polar questions present Caribbean patterns (ending with a low boundary tone L%) mixed with Andean patterns (ending with a high boundary tone H%). For the Spanish spoken in Bogotá, Díaz-Campos y Tevis McGory (2002) stated that peak alignment differs depending on the variety studied. Toledo (2007) confirms that the metrically strong syllable (or the stressed syllable) anchors to a specific tone.

In a subsequent study in 2008, Toledo analyzed the voice of Gabriel García Márquez and found that neither L*+H nor L+H* are pitch accents exclusively located in a particular place within the sentence. In the next section we examine more studies that explore the Spanish spoken in Bogotá (Hernández Rodríguez et al., 2014; M. Muñetón Ayala & Dorta Luis, 2017; Sierra Moreno, 2018; Sosa, 1999; Velásquez-Upegui, 2013). However, the exploration of other decentralized Colombian cities has started to attract the attention of researchers. For example, Buenaventura (Payeras, 2001), Bucaramanga (Roberto, 2023), Cali and Cartagena (Velásquez-Upegui, 2013), Palenque (Correa, 2017; Lopez-Barrios, 2024), and Quibdó (Mena, 2014) are contributing to the characterization of the Colombian dialects.

The current study reports on the intonation patterns and prosodic strategies used for focus marking by Spanish speakers in Pasto, Colombia. The goal is to contribute to our understanding of intonation in Colombian Spanish and to provide valuable insights into the interface between syntax and prosody.

2.2. Intonation and Focus Strategies in Spanish

In Face (2001) we find a pioneer study that explored narrow focus and annotated with Sp_ToBI. Drawing on data from 20 Spanish speakers from Madrid (5 male, 15 female), Face identified key intonational correlates of focus marking in this variety of Spanish. Notably, Face saw that narrow focus sentences showed a rising F0 in the stressed syllable (L+H*), with sentences starting at a higher pitch than usual. Additionally, an intermediate boundary tone (H- or L-) was often present immediately after the focused word, followed by a significant reduction in stress, resulting in a deaccented phrase. These findings led Face to assert the critical role of duration in narrow focus phrases.

According to Ladd (2008), the significance of focus in a word or phrase extends beyond the mere phonetic prominence of a syllable, highlighting the broader implications of focus in sentence structure. In Figure 2 we can see the sentence “Porque hoy no hay luna llena” [Because there is not a full moon today]. This sentence shows a notorious high pitch movement in the word “HOY” [TODAY], annotated as H*.

In contrast, on Figure 3 we can see the same sentence, but the high pitch movement has moved to the end of the sentence in the word “LLENA” [FULL]. We considered that the pitch accent L+H* corresponded to this word in Figure 3, because it is a rise that starts at the onset of the accented syllable and ends at the end of that syllable. The movement is also notorious because the preceding F0 presents low pitch accents (L*). In this sentence we have a case where the highlight is located at the end of the sentence, which is a typical position for broad focus sentences (Zubizarreta, 1998).

As shown in Figure 3, this sentence provides a highlight at the end, which implies that all the information before this part lacks novelty. In both Figure 2 and Figure 3, the peak of F0 (either H* or L+H*) is associated with a type of focus. In both cases, the F0 has been used to highlight important information. However, Face (2001) noted that pitch accent alone does not fully account for focus marking, as dialectal variation introduces further complexity.

On that note, Velásquez-Upegui (2013) explored dialectal intonation variation in Colombia. The results show that in Bogotá, broad focus sentences often portrait a low pitch accent (L*) at the end of sentences as reported by Sosa (1999), though occasionally shows a delayed peak (L+>H*). In contrast, narrow focus phrases consistently present a rising pitch contour (L+H*) at the end of sentences with a low boundary tone (L%). Similar patterns were observed in Cali, where broad focus phrases typically align the stressed syllable to a lower pitch accent (H+L*), sometimes accompanied by a mid-range boundary tone (M%), while narrow focus sentences feature a more pronounced descending movement followed by a high boundary tone (H%). Interestingly, in the Spanish varieties spoken in Medellín and Cartagena, both broad and narrow focus sentences share similar high pitch accents aligned with the stressed syllable, with a low boundary tone, though contour sharpness serves as a distinguishing factor.

A comparison with other Romance languages and Spanish dialects reveals parallels, such as Martín Butragueño’s (2005) findings in Mexican Spanish, where the broad focus dissimilates from narrow focus by using a high pitch contour (L+H*). Additionally, prosodic strategies like word order and boundary tones play a role in emphasis. Frota (2014) saw similar patterns in European Portuguese, where broad focus is associated with a low pitch accent (H+L*), while narrow focus phrases display a high pitch contour (H*) aligned with the stressed syllable.

D’Imperio (2001) found comparable results in Neapolitan Italian, with broad focus phrases showing a lower pitch accent (H+L*) and narrow focus phrases showing a high pitch accent (L+H*). In Face & Prieto’s (2005) revision of Sp_ToBI, they considered the contours (L*) and (L+H*) as phonological correlates closely related to broad and narrow focus, respectively. This suggests that the variations seen in Bucaramanga, Cali, and Cartagena made by Velásquez-Upegui (2013) can be allophones of these phonological contours, showing diverse patterns for broad and narrow focus across different dialects.

Vásquez et al. (2020) examined focus marking strategies in Central Mexican Spanish, finding a low pitch accent aligned with the stressed syllable as the most often used cue for Information focus. Interestingly, several cases also involved a boundary tone, suggesting that these tones may play a significant role in focus marking. Unfortunately, most studies have focused on the intonation contours at the end of sentences, leaving a gap in understanding how intonation behaves within a sentence.

Other research has explored the organization of information through dislocation and dialectal preferences. For example, Feldhausen & Lausecker (2018) studied the acceptability of left and right dislocations in three varieties of Spanish (Spain, Peru, and Argentina), finding that Argentinian speakers were more accepting of dislocations, while Peruvian speakers only accepted them if anticipatory material was present. This type of research highlights the importance of experimental data in exploring phonological phrases and focus strategies across dialects.

Building on these findings, the following section will detail the methodology used in this study, including participant selection, data collection procedures, and the specific analytical techniques employed to further investigate the intonational patterns of Spanish spoken in Pasto. By adopting a comprehensive approach, this study aims to address the existing gaps in the literature and contribute to the understanding of focus marking and intonation within this dialect.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

This article reports the preliminary findings of 4 adult Spanish monolinguals from the city of Pasto: two females and two males aged 20 to 35 years (mean = 27.23). Participants have been consistently present in the city of Pasto since childhood. Two participants graduated from university, while the other two have had basic elementary education. Participants recorded the sentences at the phonetics laboratory at Universidad de Nariño with a TASCAM DR-01, headphones, and a laptop that contained the reading task presentation. The researcher was always available in the room to provide assurance about the task, check the well-functioning of the instruments recording, and solve any question the participant had during the session.

3.2. Materials

This study gathered sociolinguistic information from participants with a modified Bilingual Language Profile (Birdsong et al., 2012), designed to self-report language history, use, proficiency, and attitudes. We used this modified online version to filter out participants who reported high proficiency in a second language. This criterion was to avoid second-language contact effects on the production of their Spanish.

We also modified a reading task used by González and Reglero (2020) to record the sentences of interest. This task consists of a PowerPoint presentation where one of the slides provides the triggering question and the AI-generated image and in the next slide participants find the answer that they need to read aloud. The PowerPoint presentation facilitated the 80 questions with AI-generated images, as shown in Figure 4.

To record broad-focus sentences, we provided trigger questions to the participants, aurally and written. The PowerPoint presentation would show a question like “¿Qué pasa aquí?” [What happens here?] with an AI-generated image for context. Then, they would touch any key in the laptop to access the next slide containing the sentence they had to read aloud. In this case it was “Los hermanos preparan la comida” [The brothers prepare dinner]. After reading aloud, participants pressed any key on the computer to move at their own pace to the following slide until the presentation ended.

Similarly, we designed slides that prompted narrow-focus sentences to emphasize a specific part of the sentence. For this purpose, we used information questions like “¿Quién/Quiénes?” [Who?] to trigger answers with a focus on the subject. For instance, in the question “¿Qué compraron los alumnos?” [What did the students buy?]. The answer, shown in Figure 5, had a focus on the subject, as in “LOS ALUMNOS compraron la granola” [THE STUDENTS bought the granola].

Meanwhile, we used information questions like “¿Qué?” [What?] to trigger sentences with a focus on the object. For instance, in the question “¿Qué compraron los alumnos?” [What did the students buy?] where the emphasis is located at the end of the sentence, like: “Los alumnos compraban LA GRANOLA” [Students bought THE GRANOLA]. By having the same sentence for a different question, we were able to collect identical sentences with different focus. Another consideration when designing the reading task was to consider words with an acute accent on the next to the last syllable and whenever possible avoiding words with consonants like p, t, and k (stops) or s or f (fricatives) as these sounds usually interrupt the flow of the contour of the voice. Also, we created AI-generated images to procure the anonymity of the people shown in the task and provide images that were free to use.

3.2. Data Analysis

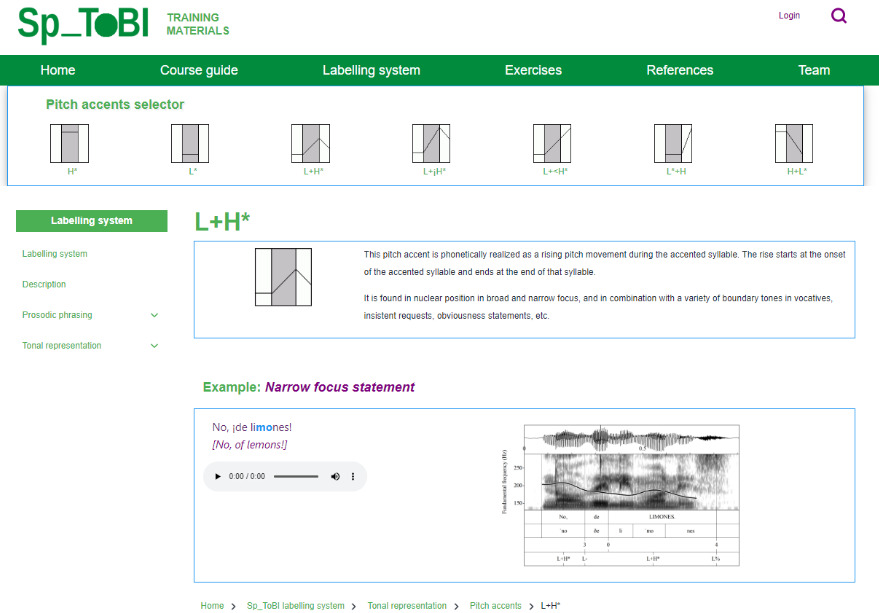

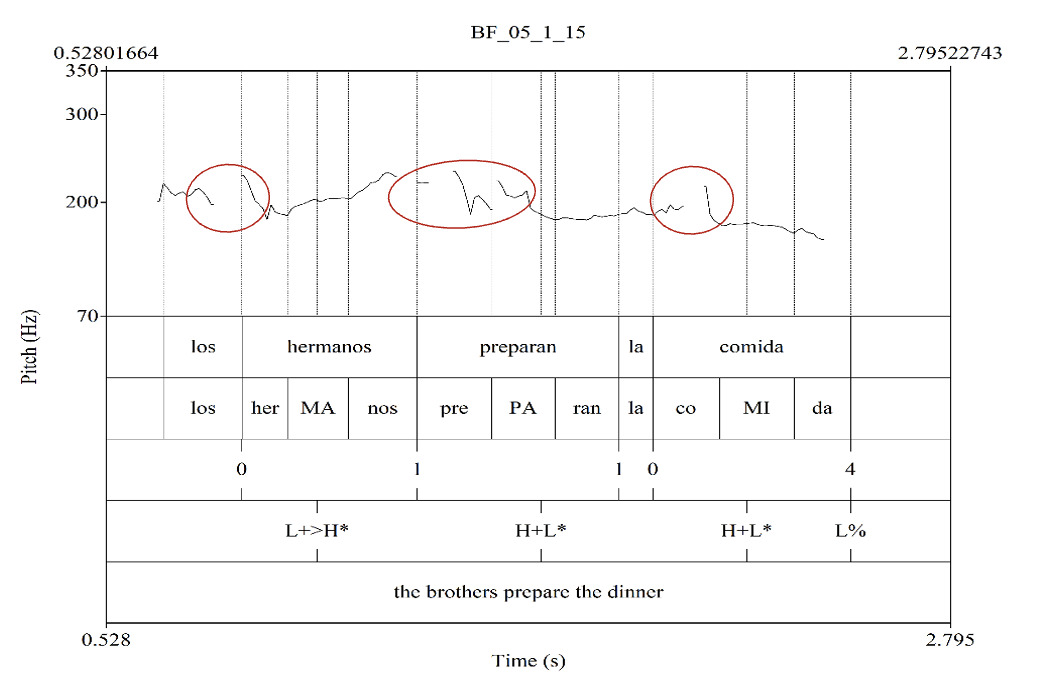

Overall, each participant recorded a total of 80 sentences, 15 were broad-focus, and 30 were narrow-focus (15 on the subject and 15 on the object). The other 40 sentences of the reading task include distractors and contrastive sentences that will be considered for future publications. Thus, this study provides the preliminary findings of 60 sentences with broad-focus, 60 sentences with narrow-focus on the subject and 59 sentences with narrow-focus on the object. The contours found in these sentences were annotated following the Sp_ToBI labels (Aguilar et al., 2024) as shown below on Figure 6.

By using the software Praat (Boersma & Weenik, 2024), we annotated the pitch accents located in three different parts of the sentence: in the subject, in the verb and in the object. Figure 6 contains a typical image of Praat and the way we organize and analyze information in this software. Each of the lines under the F0 includes varied information. The first one has every word within the sentence, the second one includes the syllabification of the words to identify the acute accented syllable (spelled in capital letters). Line three contains numbers indicating the divisions between words, and line four contains the Sp_ToBI labels. On line five, a miscellaneous space, contains the full phrase in English.

Figure 7 shows a screenshot of an excel sheet where we organize the labels identified in Praat. The first row consists of the names of the columns. We have columns for the number of the PowerPoint slide, the full sentence with its code, its focus classification, a shortcut code, and the pitch accents identified and miscellaneous notes. This image corresponds to the NFO (narrow-focus on the object) sentences page.

Figure 7 shows an excel sheet that contains ten pages. The pages are visible on the bottom line of the image. The last three correspond to the broad-focus sentences, the narrow-focus on the Object and the narrow-focus on the Subject. The other pages with numbers correspond to participants, and each page contains the information of the 80 sentences that participants recorded with the reading task. We use this Excel sheet to organize by categories of interest and calculate the frequency of a contour in relation to the type of focus. In the next section, we share the preliminary results with the recurrence of intonation patterns based on frequency, an image with a representative sentence and a bar chart.

4. Results

In this section we present the results of our analysis regarding the intonational contours identified in the speech of 4 speakers from Pasto. We report the patterns found in 179 sentences analyzed in three subdivisions. The first one concerns the sentences with broad-focus. The second subdivision contains the results of the sentences with narrow-focus on the subject. Finally, the third subdivision reports on the sentences with narrow-focus on the object. Each subdivision contains a sample sentence and a bar chart with the pitch accent frequency.

4.1. Broad Focus Sentences

We obtained these types of sentences by using questions like "¿Qué pasa en la imagen? [What happens in the image?]. This section reports on 60 sentences with broad-focus. Figure 8 shows the spectrogram of the sentence “Los hermanos preparan la comida” [The brothers prepare dinner]. The acoustic representation of the intonation of this sentence is observable on top of the sentence as a line that starts around 200Hz, rises during the word “hermanos” [brothers], and from there, the line slowly drops down until the end of the sentence. This line is the F0, the physical manifestation of the melody of the voice. Notice that the highest point of F0 does not align with the stressed syllable “MA” in “hermanos” [brothers]. Hualde (2013) described this contour as a delayed peak (L+>H*). The following pitch accents, in the verb and in the object, correspond to a low contour (H+L*). The final boundary tone is also low (L%). Overall, the F0 in this sample presents a decreasing movement without harsh movements or special emphasis along the sentence.

However, there are micro-melodic effects that interrupt the F0. Those consist of the voiceless plosive segments in this sentence. For example, the circles in Figure 8 are highlighting these interruptions caused by fricatives, like in “los” [the], and in “hermanos” [brothers], or stops like in the words “preparan” [they prepare] and “comida” [food]. Other than these expected breaks in the F0, the contour shows a continuous decreasing movement.

Below, on Figure 9, there is a bar chart that summarizes the broad-focus contours present in this study. The delayed peak (L+>H*) contour was clearly the most frequent contour in subject position. Yet, the diverse contours in the verb position does not allow to identify a pattern. Verb contours include delayed peaks (L+>H*), low-high (L+H*) and high-low (H+L*) pitch accents, low-high with intermediate boundary tones (L+H* H-), high-low with high and low intermediate boundary tone (H+L* H-) and (H+L* L-), low with intermediate boundary tones (L* L-) and just low (L*). With such a catalog, it is important to continue analyzing more sentences to determine a pattern. Lastly, we identified a clear low-high pitch accent (L+H*) as the most frequent contour in object position.

Figure 9 presents the most common pitch accents found in the broad-focus sentences analyzed. The delayed peak contour (L+>H*) was the most frequent in the 35 subjects, followed by the low-high with intermediate high tone (L+H* H-). These two labels describe a similar pattern: a rising peak that fully develops in the post-accentual syllable. However, no clear pattern emerged for the 56 verbs analyzed, which exhibited a variety of contours, including delayed peaks (L+>H*), and contrasting contours like low-high (L+H*) and high-low (H+L*), along with combinations involving intermediate boundary tones. In contrast, the 59 objects analyzed showed an apparent preference for the low-high (L+H*) pitch accent, with 34 instances, followed by the high-low accent with 16 cases. Overall, while distinct patterns emerged for the subject and object in broad-focus sentences, the verbs deserve special attention in future research.

4.2. Narrow Focus on the Subject

When a sentence works with narrow-focus, part of the information contained in it receives a special intonation emphasis. In Spanish, the syntactic structure allows to allocate this part at the end of the sentence (Zubizarreta, 1998). However, in this study we are trying to see the strategy of emphasis in situ, which means putting emphasis on the subject without displacing it to the end of the sentence. To do so, we assessed two sentences that are almost identical but with different focus. In Figure 10, the sentence “LOS ALUMNOS compraron la granola” [THE STUDENTS bought the granola] responds to the question “¿QUIÉNES compraron la granola?” [WHO bought the granola?]. The F0 in this sentence provides an acoustic cue about the emphasis on the subject.

Similarly to the previous example, in Figure 10 the syllable “LUM” in “alumnos” [students] was label as a delayed peak (L+>H*). This describes a steep rise in this syllable that achieves its higher peak in the postaccentual syllable. We annotated the pitch accent in the verb and object with a high-low contour (H+L*). This means that after the peak in the previous word, all that comes after is a continuous descend. Finally, we labeled the boundary tone with the low annotation (L%).

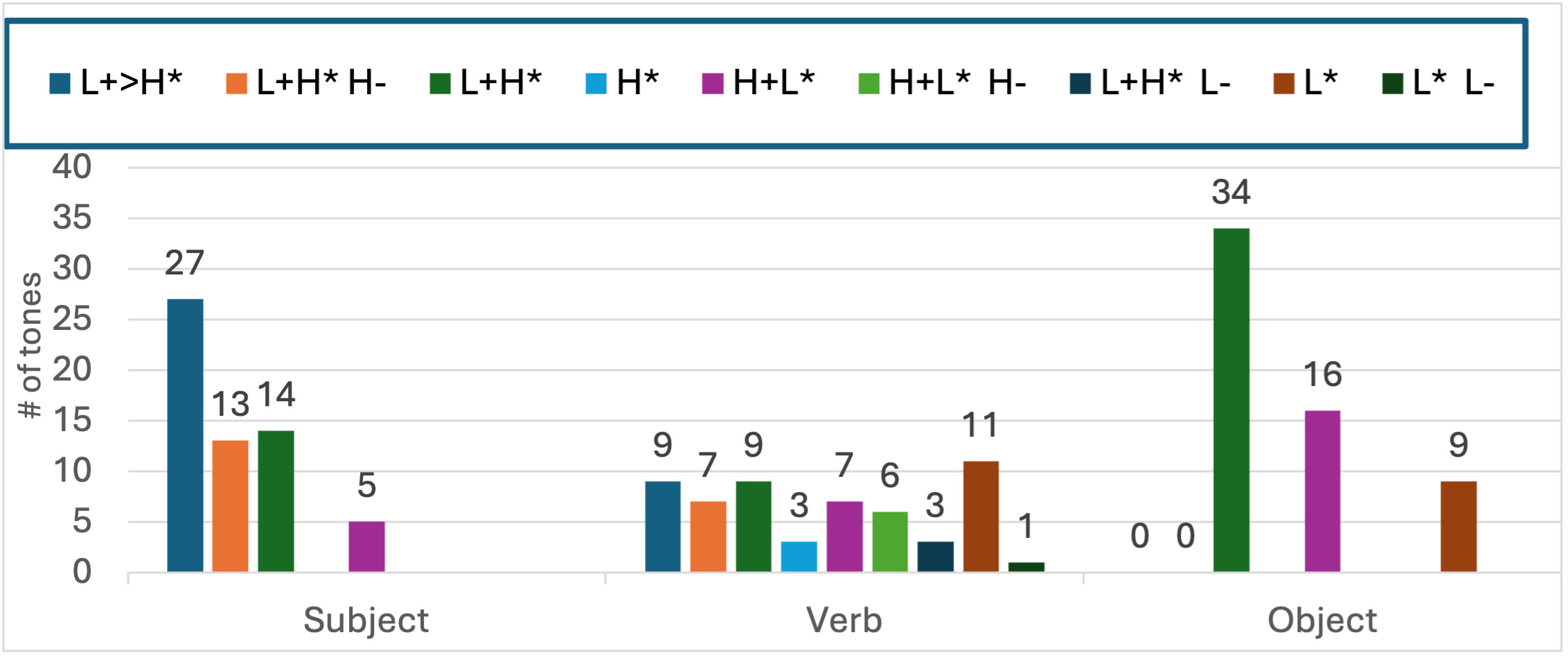

Figure 11 shows the contour frequencies found overall in the sentences with narrow-focus on the subject. From 59 subjects analyzed, the delayed peak contour (L+>H*) remains as the most frequent contour with 29 tags in this location, followed closely by the low-high tone (L+H*) with 22 tags. Regarding the pitch accent in 52 verbs analyzed, the variety of contours is too broad to determine the pattern in this location. For the 48 objects analyzed, the high-low tone (H+L*) was the most common annotation with 26 appearances.

The frequency of different contours found in verb position and shown in Figure 11 makes it exceedingly difficult to establish the trend in this location. In sum, there are delayed peaks (L+>H*), rising tones (L+H*), diverse boundary tones (L+H* H-), (H+L* H-), (H* H-), (L* H-), and decreasing tones (H+L*) and (L*). The array of patterns seen for the verbs in narrow-focus on the subject provides the same challenge to understand what the tendency is, just as it happened in the broad-focus sentences.

4.3. Narrow Focus on the Object

While the previous section the sentence answered the question “¿Quiénes?” [Who?], here the sentence corresponds to the question “¿QUÉ compraron los alumnos” [WHAT did the students buy?]. In this case, the F0 provides acoustic cues about the emphasis at the end of the sentence. Figure 12 shows the sentence “Los alumnos compraron LA GRANOLA” [The students bought THE GRANOLA]. As previous examples, we labeled the subject with a delayed peak contour (L+>H*) and the verb with a high-low pitch accent (H+L*).

Regarding the annotation for the object in Figure 12, we verified if this movement was perceptually significant, as the movement is not visibly discernable. To confirm if it corresponded to a low-high pitch accent (L+H*), we calculated the difference in Hertz between the beginning and end of the syllable “NO” in “granola” [granola]. This syllable started at 175Hz and ends at 275Hz. We converted this 100Hz increase to semitones and determined it to be 7,8 semitones. This surpasses the perceptual threshold, which corresponds to 1.5 semitones (Martínez Celdrán & Planas, 2003; ’t Hart et al., 1990). Consequently, we agreed that this contour’s label was a low-high pitch accent (L+H*).

This pitch accent in the object agrees with previous descriptions of a typical narrow-focus sentence (Face, 2001). To accurately label this pitch, we calculated the equivalent semitones of the Hertz shown in Praat. As in the previous sentences, the boundary tone is also low (L%). Figure 13 summarizes the common pitch accents found for sentences with narrow-focus on the object. As in the previous examples, the delayed peak (L+>H*) is the most common contour in the subject.

Remarkably, sentences with a narrow focus on the object favor a low-high pitch accent (L+H*) in the verb position. Second to this contour, we identified 12 verbs with low-high pitch accent contours and a high intermediate boundary tone (L+H* H-). The object in this type of sentence also favors a low-high pitch accent (L+H*).

This time, the bar chart for narrow-focus on the object presents clearer patterns of pitch accents. Out of 57 subjects analyzed, 32 of them favor the delayed peak (L+>H*) as in the previous focus sentences. Regarding the 51 verbs analyzed, the pitch accents in this location are varied, but the low-high pitch accent (L+H*) is present in 16 of the cases. And, out of the 56 objects analyzed, 27 showed a low-high pitch accent (L+H*).

To sum up, the most frequent contour in the subject position is the delayed peak pitch accent (L+>H*) independent of the type of focus. In verb position, the patterns were inconclusive as there were no clear trends. However, there is a potential exception in the sentences with narrow focus in the object. These favor low-high (L+H*) pitch accents. Concerning the object, participants also prioritize the use of low-high pitch accent (L+H*). Based on these results, we need to analyze a bigger sample to understand the patterns hidden in verb position and to suggest a latent interpretation of focus based on the contours present within the sentence. In the following segment we discuss and contrast these findings with earlier research.

5. Discussion

This study shares the preliminary findings about the intonation of the Spanish spoken in Pasto. The goal was to identify intonation patterns and examine the strategies used to differentiate between new and old information. To achieve this, we analyzed 179 sentences with broad and narrow focus (subject and object). Four Spanish monolingual speakers from Pasto recorded the sentences by following the instructions of a reading task. We annotated these audio samples with the Sp_ToBI labeling system (Aguilar et al., 2009; Estebas Vilaplana & Prieto Vives, 2008; Hualde & Prieto Vives, 2016) on Praat. We classified and organized the contours in an Excel sheet to identify the patterns in each case. This section is divided into four parts. The first one considers the contours observed in the subject of the three types of focus sentences with broad and narrow focus. The second part reviews the results of the typical contours in the verb position. The third part interprets the contours of objects and compares them with previous studies. Finally, the fourth section considers the limitations of this study.

5.1. Subject Contours in Pasto

In this section, we considered the contours observed in the subject of three focus types to identify the patterns displayed at the beginning of sentences. The subject offered the opportunity to analyze the contour used by broad-focus sentences and narrow-focus sentences. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, we created sentences with a narrow focus in situ as well. This means that we analyzed words that responded to questions like “¿Quién/Quiénes?” [Who?] and triggered responses where the subject was the narrow-focus of the sentence and stayed in its position at the beginning of the sentence. We wondered if there were acoustic cues related to these focus cases.

The results indicate that the most common label in the subjects is the delayed peak (L+>H*) regardless of focus type. This lines up with previous studies, such as Hualde’s (2013) description of broad-focus intonation, where the delayed peak also appears prominently. Measuring the amplitude of this pitch accent may provide physical evidence to identify the use of this contour in different focus intentions. We consider that measurements like pitch range and duration would provide more phonetic cues to characterize a type of sentence according to the focus. The difference would be related to intensity, being more prominent on those sentences with narrow-focus on the subject as noted by Face (2001).

5.2. Verb Contours in Pasto

Regarding the intonation patterns seen in the verbs, they provide to be a challenge as the number of configurations is considerable. In broad-focus statements, the 56 verbs analyzed display delayed peaks (L+>H*), rising pitch accents (L+H*), (L+H* H-), (H*), and a decreasing pitch accents like (H+L*), (L*), along with combinations involving intermediate boundary tones (H+L* H-), (L+H* L-). In narrow-focus on the subject the situation is similar, verbs show monotones like (H*) and (L*), ups and downs (L+H*), (H+L*), delayed peaks (L+>H*), and combinations with intermediate boundary tones as well (L+H* H-), (H+L* H-), (L* H-) or (H+L* L-). In both, the broad-focus and narrow-focus on the subject, the frequency fails to provide a pattern. It is indistinguishable.

On the other hand, verbs in sentences with a focus on the object start to show a trend. The most common configuration is the low-high pitch accent (L+H*). Yet, this frequency represents 26% of the verbs analyzed in this focused category. The other contours consist of the same varieties as the other types of focus. We also noticed that verbs generally present more diverse arrangements than the contours present in the subject or object. This means a broader use of intermediate boundary tones (H-), (L-) and monotones (H*), (L*) compared with the other locations in the sentence.

5.3. Object contours in Pasto

Objects in sentences with broad-focus behave similarly to the sentences with narrow-focus in the object. Both display a low-high pitch accent (L+H*) in the object. However, there is a prominent difference between the narrow-focus on the subject and the narrow-focus on the object. While sentences with narrow-focus on the subject often presented a high-low contour (H+L*) in the object position, the sentences with narrow-focus on the object showed an aligned peak tone (L+H*) in the object position. This difference is considerable between the two as they both describe opposite movements of the F0. However, it presents a tricky situation between the broad focus sentences and the narrow focus on the object, as they behave similarly. We consider that the unmarked syntactic structure of the Spanish language is the reason. In this structure, the last word of an utterance bears foremost importance in the organization of the information, as it will have the focus due to its location at the end (Zubizarreta, 1998). Also, using intensity and other suprasegmental tools like the intermediate boundary tone may play a part in the strategy of organizing known vs unknown information.

In other studies, objects present similar contours depending on the focus type. For example, Cuzco sentences (Van Rijswijk & Muntendam, 2014) and Ecuador sentences (O’Rourke, 2010) with narrow focus present a low-high pitch accent (L+H*). But Ecuador sentences with broad focus display a low pitch accent with a boundary tone (L* L%) while in the sample of Pasto it shares the same contour as the narrow focus low-high pitch accent (L+H*).

Table 1 summarizes and presents the typical contours identified in the 179 Pasto Spanish sentences analyzed for this report. It illustrates the three points of interest on the top row: subject verb and object. It also shows the three types of focus on the left column: broad, narrow focus on the subject and narrow focus on the object. The pitch accents portrayed represent the most common contour found in each of the intersections.

We summarize the preliminary findings on Table 1, here, the subject shows the same delayed peak (L+>H*) in three types of focus. Verbs contain a question mark in the broad focus and the narrow focus on the subject. This corresponds to the challenge of identifying a pattern among the diverse contours present in this part of the sentence. It also represents the potential study areas that can help understand information organization. The object uses two pitch contours, the low-high (L+H*) associated with broad and narrow focus on the object, and a high-low (H+L*) associated with focus of the subject in situ. With this results, our goal is to provide preliminary results and stimulate the exploration of the problematic areas identified in this study.

6. Limitations

The ongoing exploration of Spanish intonation in Pasto contributes to the understanding of how speakers use intonation to convey new information, known information, and in-situ emphasis. However, intrinsic factors constrain this area of study. One, the analysis of intonation is highly time-consuming, making it a slow process to understand how the F0 assists in the organization of information during speech. Second, this time-consuming task also limits the number of participants included in such studies, affecting the generalization of the results to the broader population due to the small sample sizes. Third, this also hinders the report of sociolinguistic factors and their effect on intonation. Even though the participants contributed with information about their sex, age, education, linguistic attitudes and socioeconomic status, the results of the effects of these sociolinguistic variables will provide more robust significance in a future report where more participants are analyzed.

Other limitations are related to the annotation system, and lack of information to compare. Despite Sp-ToBI being a consistent label system, it does not provide information about the amplitude or duration of intonation contours. We can improve the accuracy of our results by measuring the pitch range and duration to complement the label system. Regarding the limited report on prenuclear accents in intonation studies, this is a limitation that we can supplement by providing access to our results and encouraging researchers to report the pitch accents observed during the F0 transition from the beginning till the end of the entire sentence. Prenuclear accents are those located before the last word of a sentence and, in this context, would refer to the pitch contours in the subject and object. Habitually, researchers provide an inventory of the nuclear pitch accent, located at the end of a sentence, with the final movement of F0. Those are the results we can compare with now.

Another limitation is the audio sample quality. The study of intonation often relies on laboratory samples, which require recording in a controlled environment, as the impact of background noises affects the quality of the F0. An additional constraint is the inhibition participants experience in a controlled laboratory setting. This environment affects participants’ spontaneity, limiting natural or spontaneous speech recording. These limitations should encourage researchers to propose creative ways to explore the human voice. With steady work, linguists can contribute to the growing field of Hispanic studies, understanding acoustic phenomena and identifying the workings of oral information organization.

7. Conclusion

The preliminary findings of this study offer valuable insights into the intonation patterns of Spanish spoken in Pasto, Colombia, particularly in relation to three different focus conditions: broad focus, narrow focus on the subject, and narrow focus on the object. The observed use of delayed peaks in broad focus sentences concurs with earlier descriptions, confirming the tendency of delayed peaks in broad focus contexts. However, the presence of delayed peaks across all focus types, including narrow focus sentences, suggests that this intonational feature is not exclusive to broad focus, but rather a more complex phenomenon that may vary in prominence depending on the specific focus condition.

Furthermore, the study highlights the variability in intonation patterns associated with verbs, particularly in narrow focus on the object, where peak alignment within the stressed syllable appears more often. This suggests that the intonation of verbs could function in discriminating between narrow focus on the subject and narrow focus on the object. Additionally, the contrast in intonation contours at the end of sentences with narrow focus on the subject versus on the object (H+L* versus L+H*) underscores the importance of final contour patterns for marking focus in Spanish.

These preliminary findings also complement results reported for Mexican Spanish, where Vasquez et al. (2020) found that boundary tones reflect focus. In contrast, Gabriel (2010) shows that the strategies varied across dialects in Argentinian Spanish, making it a pattern associated with regional preferences. These findings contribute to a growing body of Hispanic research that explores regional variations in intonation, complementing observations made in other territories. The similarities and differences across Hispanic-speaking areas emphasize the need for continued research into the role of intonation in focus marking and how regional preferences influence these patterns.

Future studies should aim to include a larger and more diverse sample of speakers to enhance the reach of the findings. Increasing the number of participants would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the intonational patterns and their variations within different sociolinguistic factors. This study suggests that verb intonation may play a role in distinguishing between diverse types of narrow focus. Future research should examine how verb intonation interacts with the type of focus and whether specific patterns exist. By addressing these areas in future research, scholars continue to build on these preliminary results contributing to a better understanding of Hispanic studies in intonation and its role in communication and focus.