… En aquel Imperio, el Arte de la Cartografía logró tal Perfección que el mapa de una sola Provincia ocupaba toda una Ciudad, y el mapa del Imperio, toda una Provincia.

Jorge Luis Borges

Mapa Fílmico de un País (2012-present) is a digital collection of more than 250 short documentaries by dozens of filmmakers that comprises a participative, diverse, and self-reflexive cinematographic atlas of post-Transition to Democracy Chile.[1] Mapa Fílmico is the foundational project of the not-for-profit and cinema-centric organization MAFI, also known as Fundación MAFI and Mafi.tv.[2] The “microdocumentales” (Aravena Abughosh and Pinto Veas 13; Girardi 8; Lagos Labbé 165) of Mapa Fílmico incorporate three cinematographic techniques: a single static shot, direct sound, and a short duration (less than three minutes in length).[3] Many Mapa Fílmico works are exhibited on the organization’s website Mafi.tv and across its social media and streaming accounts. Others are posted exclusively on social media.[4] These films—shot between 2010 and 2020—capture aspects of life from across the country including popular religious practices, Mapuche culture, the impact of immigration, and environmental issues. They also document moments of societal upheaval like the nation-wide protests in late 2019 in which demonstrators demanded an overhaul of the country’s constitution and economic structure. In their varied representation of Chilean society via a set of well-defined formal strictures, these short films exemplify John Grierson’s definition of documentary filmmaking as “the creative treatment of actuality” (216).[5] And in their cartographic presentation and construction, they epitomize Giuliana Bruno’s observation that “film is modern cartography. It is a mobile map” (24).

MAFI was founded in 2011 by the filmmakers Christopher Murray, Antonio Luco, Pablo Carrera, and Ignacio Rojas. The organization operates a film production entity, a digital distribution platform, short-term film workshops, and longer-duration residency programs. Although MAFI has produced stand-alone documentary films, its first and most well-known project is Mapa Fílmico.[6] The short films of Mapa Fílmico depict life throughout the country, from the Atacama Desert in the north to Patagonia in the south. This emphasis on documenting life across the geographically varied country represents a counterpoint to its highly centralized political structure in which the regions are subordinate to a President and administrative state based in Santiago. However, reflecting the size and concentration of economic, political, and cultural power in the capital, the majority of these films were shot within the Santiago Metropolitan Region.[7]

MAFI founded its online platform Mafi.tv in 2012 with forty short documentaries that form the bedrock of Mapa Fílmico (Buschmann 7).[8] That same year, MAFI participated in the prestigious International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA). A curated selection of films from Mapa Fílmico screened as part of the digital media-focused IDFA DocLab program. According to Diego Pino, the Director and Executive Producer of MAFI, the exhibition at IDFA in 2012 represented MAFI and Mapa Fílmico’s global launch (Pino, “Personal Interview”). The trailer for the collection of Mapa Fílmico shorts shown at IDFA describes “A growing network of filmmakers—capturing fragments of Chilean reality—creating a filmic map of a country” (IDFA 2012). Early in its existence, MAFI invited directors to make films for the project. Later, filmmakers could submit their own documentaries or proposals to MAFI for consideration.

A page titled “Sobre MAFI” on MAFI’s website serves as a kind of mission statement for the organization. It emphasizes a self-aware engagement with Chile: “MAFI [. . .] es una organización sin fines de lucro dedicada al registro documental con el objetivo de contribuir a la memoria audiovisual del país y fomentar la reflexión social en base a imágenes.” The document also underscores the organization’s desire to cultivate active spectators: “La mirada MAFI se caracteriza por capturar fragmentos documentales que invitan a detenerse a mirar, reivindicando el valor expresivo de la imagen como forma de pensar la realidad” (“Sobre MAFI”). Pablo Carrera, a filmmaker and founder of MAFI, describes the use of a single static shot, direct sound, and brevity as an effort to “volver a lo más esencial del lenguaje audiovisual” (Buschmann et al. 1). In the same vein, Diego Pino says Mapa Fílmico is designed to make viewers experience Chile through a critical lens: “lo que viene a proponer es ver las cosas que vemos a diario, pero desde otro punto de vista, desde otro espacio” (Pino, “Personal Interview”).

Alongside its Mapa Fílmico project, MAFI operates workshop and residency programs for aspiring filmmakers of various ages and professional backgrounds in Chile and abroad.[9] These local and international workshops exemplify MAFI’s emphasis on technology, digital distribution, and creating a “red de realizadores” (“Sobre MAFI”). The Escuela MAFI workshop program was established in 2013 and aims to educate participants across the country in filmmaking techniques.[10] A typical workshop lasts five days. The first three days are dedicated to theory and technical instruction, the fourth to shooting, and the final day to editing and postproduction. A call for applications for a 2015 Escuela MAFI workshop in Santiago emphasizes developing theoretical and practical tools for making cinema:

El taller, de cinco jornadas de duración, está orientado a personas que deseen iniciar un camino en el audiovisual y el documental. Esto, a través de la entrega de herramientas teóricas y prácticas, para observar la realidad desde lo audiovisual; comprender conceptos básicos de lenguaje cinematográfico, edición y sonido y, muy especialmente entrenar la mirada. (MAFI, “Escuela MAFI Santiago”)

With their emphasis on learning through practice, these workshops evoke the classes imparted by Alicia Vega to a group of children in a Santiago población in Ignacio Agüero’s Cien niños esperando un tren (1988). And similar to the climatic excursion to a movie theater at the end of Agüero’s film, many MAFI workshops conclude with a screening of participants’ films.

In addition to its workshops, MAFI hosts longer-term residency programs in communities across Chile. Participants live in the community for two to three months and collaborate with the local community on film projects (Pino, “Personal Interview”). MAFI has held residencies in Petorca (2015), Melipeuco (2016), Puente Alto (2017), and Cerro Sombrero (2018-2019).[11] Christopher Murray describes these residency programs as opportunities for fomenting collaboration: “No queríamos que la experiencia se quedara en la web o en un grupo de realizadores, sino que se conectara con los territorios y que hubiese un diálogo y trabajo colaborativo con las comunidades” (Arcaya, “Chile en un mapa-documental”). MAFI’s work with the local community evokes the Nobel-prize winning author Gabriela Mistral’s 1930 article “Cinema documental para América.” Mistral advocates for the creation of a pan-Latin American Instituto del Cinema Educacional designed to foment the spectatorship and creation of home-grown documentaries.[12] Through its filmic map, workshops, and residency programs, MAFI functions like a contemporary version of Mistral’s proposed institute, bringing real-world and digital collaborations to local communities.

MAFI and its Mapa Fílmico coincide with what María Paz Peirano calls “un momento bullente del cine documental en Chile” (64). Peirano attributes the flourishing of Chilean documentary cinema from the Transition to Democracy period through the 2010s to a variety of institutional factors, most notably state support for cinema and the development of a local and international infrastructure to support Chilean filmmakers:

Parte de este éxito se debe a la reconfiguración de las formas de producción, circulación y exhibición del cine documental en el país, ligado la expansión de la institucionalidad cultural y fondos públicos para su desarrollo (Fondo Fomento Audiovisual, CORFO, y fondos del Consejo Nacional de Televisión), la creciente profesionalización del campo en nuevas escuelas especializadas en cine y audiovisual, la formación de redes de trabajo y plataformas de distribución (ChileDoc y Miradoc), el aumento y especialización de los espacios de exhibición (festivales de cine y salas de cine no comerciales) así como su creciente internacionalización, asociada a una constante participación del cine chileno en el circuito de festivales y mercados internacionales para el documental. (64–65)

The consolidation of Chile’s cinematic infrastructure in the post-Transition period is also marked by active government engagement with the country’s film sector. MAFI’s varied activities in the areas of production, distribution, exhibition, and pedagogy align with the Chilean government’s ambition to expand the nation’s film industry and cultivate audiences for local cinema. The 2016 report Política Nacional del Campo Audiovisual 2017-2022, published by the Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes (CNCA), establishes the state’s three-pronged policy towards the film industry, which emphasizes participation, development, and authorship rights. The report advocates for the state taking an active role in fomenting an inclusive industry that reaches beyond Chile’s borders:

[…] esta Política deberá comenzar a generar las condiciones que permitan un desarrollo equitativo, participativo, sustentable y respetuoso de la diversidad cultural, de los derechos individuales y sociales y de las realidades regionales, para proyectar con fuerza las grandes virtudes profesionales y creativas del campo audiovisual, tanto a nivel nacional como internacional. (13)

The work of MAFI and its Mapa Fílmico exemplify this decentralized cinematic model by offering a wide lens view of Chilean society beyond the capital Santiago. Through its in-person film workshops and residencies, as well as its use of online distribution channels, MAFI provides a model for cultivating filmmaking talent and reaching audiences inside and outside of Chile.

Alongside expanding state and private sector support for Chile’s film industry in recent years, the foundation and development of MAFI also coincide with the emergence of an online film culture in Chile. Among the notable manifestations of this burgeoning digital film culture are the Chilean film encyclopedia Cinechile (established in 2009), author and filmmaker Alberto Fuguet’s distribution and exhibition platform Cinépata.com (2009-2014), the digital film archives of the University of Chile and the Cineteca Nacional de Chile (established in 2012 and 2013, respectively), the government-sponsored streaming platform Onda Media (established in 2017), and the entrance of U.S.-based streaming and production giant Netflix into the country in 2011. Additionally, MAFI overlaps with contemporary digital, multimedia, and interactive film projects by Chilean filmmakers, including Pablo Ocqueteau and Philine von Düszeln’s Aysén Profundo (2010-2012), which documents life in the Patagonian region of Aysén through cartoons, drawings, videos, and music; Rosario González’s film essay V.O.S.E. (2014), which uses archival footage, interviews, and voice-over narration to explore how subtitles shape film spectatorship; and the Colectivo Registro Callejero[13], a filmmaking collective formed in October 2019 with the goal of documenting the wave of protests against the Chilean government demanding far-reaching political, economic, and social reforms.[14]

Taking a longer view of Chilean film history, Mapa Fílmico forms part of an established and multifaceted national tradition of documentary filmmaking. Jacqueline Mouesca observes that Chilean documentary filmmaking is closely connected to the formation of a national identity and memory. Comparing narrative and documentary filmmaking Mouesca notes, “a la hora de tener que reconstruir los perfiles de un período histórico, o incluso de la historia de una nación […] es bastante probable que el documental nos ofrezca más posibilidades de apoyo para la memoria. No es difícil constatarlo en el caso de Chile” (11). The use of cinema to document Chilean life and culture dates back to early 20th-century films like Maurice Saturnin Massonnier’s portrait of a crowd at a Valparaíso beach in Un paseo a Playa Ancha (1903) and Salvador Giambastiani’s depiction of miners at the Teniente copper mine and the neighboring town of Sewell in El Mineral El Teniente (1919).[15] However, perhaps the closest historical precedent to Mapa Fílmico are the short documentaries of filmmakers associated with the Centro de Cine Experimental from the late 1950s to early 1970s.[16] In a 1962 article in Ecran, Sergio Bravo, a filmmaker and founder of the Centro de Cine Experimental, underscores the open nature of the initiative: “Cine Experimental no trabaja tan solo con sus nueve componentes. Así cualquier persona que tenga interés en filmar y presente un buen tema, obtiene el apoyo necesario para desarrollarlo” (qtd. Cortínez and Engelbert 84-85). A similar emphasis on collaboration with a range of filmmakers runs through MAFI. And like the Mapa Fílmico microdocumentaries, the Centro de Cine Experimental short documentaries Mimbre (Sergio Bravo 1957), Testimonio (Pedro Chaskel, 1969) and Venceremos (Pedro Chaskel and Héctor Ríos, 1970) depict an unequal and rapidly changing society through a self-reflexive lens.

A more recent production which shares much in common with the Mapa Fílmico is the “microprograma documental” series Mi Patrimonio (2019-2020), which first aired on Televisión Nacional de Chile. This series documents Chilean culture and traditions—some of which are also featured in the Mapa Fílmico— through very short documentary films. And like MAFI, Mi Patrimonio aims to “crear un mapa audiovisual de alta calidad de paisajes y culturas a lo largo y ancho del país” (Programa Mi Patrimonio). The program features episodes on topics like the Cuasimodo rite, the life of a lanchero in Patagonia, a cinema in the southern town of Porvenir, and an all-women cueca dance troupe in Santiago. Through their use of microdocumentaries to capture a wide-range of experiences and social practices, Mapa Fílmico and the Mi Patrimonio offer quilt-like portraits of Chile, in which viewers are encouraged to make connections across films.

A cinematographic atlas

In its representation of Chile through dozens of short documentaries compiled together in the form of a digital map, Mapa Fílmico parallels a specific kind of cartographic genre: the atlas. J.B. Harley and David Woodward define maps as “graphic representations that facilitate a spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes, or events in the human world” (xvi). The atlas is a genre of maps distinguished by a series of conventions and practices. Teresa Castro maintains that atlases “constitute a collection of maps (i.e. images) assembled in relation to an overall scheme that aims for thoroughness and completeness. In this sense, they resemble world maps, but unlike them, atlases demand to be browsed and navigated” (9). Although atlases predate cinema, both mediums incorporate montage and juxtaposition as fundamental features. Castro notes that a distinguishing feature of atlases is their use of montage to create a whole out of many pieces: “atlases refer as much to a strictly cartographic instrument as to a graphical means for the assemblage and combination—if not montage—of images” (13, author’s emphasis).

Christian Jacob observes that the atlas differs from the world map in its archival function: “the multiplicity of maps turns it into an archive in which all the geographical knowledge of a period may be recorded. Every atlas is a summa that monumentally sets in place the current condition of the world or one of its regions” (67). Like all archives, the atlas invites critical engagement by the viewer and serves as “an object of reflection and debate” (Hall 89). Through its portrayal of the multiplicity of experiences in contemporary Chile, Mapa Fílmico embodies the archival nature of the atlas. MAFI and its Mapa Fílmico are not the only manifestations of this archival impulse in recent Chilean filmmaking. In his documentary La cordillera de los sueños (2019), the renowned Chilean documentarian Patricio Guzmán observes that emerging contemporary Chilean filmmakers are creating their own archives of memory: “Hoy día, en todo Chile, hay muchos jóvenes cineastas que filman en todas partes. Entre todos ellos escriben la memoria del futuro” (1:17:11-1:17:26).[17] With their dedication and inclusive approach to documenting life in Chile, MAFI filmmakers and the Mapa Fílmico play a key role in creating and preserving these national memories.

Mapa Fílmico’s depiction of the geography and social customs of Chile, formal elements, and self-reflexive qualities represent common threads with an earlier atlas of Chile: Claudio Gay’s two-volume Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile (1854). Gay’s Atlas is a foundational document of the Chilean nation. It features 315 illustrations by the author and other artists that depict the country’s natural history, geography, politics, economy, and customs.[18] In 1830, the Chilean government contracted the French-born naturalist to begin work on an extensive project of recording the country’s flora, fauna, and people. Gay travelled throughout Chile between 1830 and 1842, documenting his observations in notes, letters, and sketches. After returning to Europe, Gay published his twenty-eight-volume Historia física y política de Chile between 1844 and 1871.[19] Gay’s Atlas serves as an essential visual complement to his Historia.

The first image of the Atlas is a lithograph portrait of the authoritarian leader Diego Portales, who played a central role in the consolidation of the Chilean state and championed Gay’s ambitious project.[20] Portales’s likeness is followed by a series of fifteen maps, including a full-scale, fold-out map of Chile titled Mapa para la Inteligencia de la Historia Física y Política de Chile.[21] In between maps and representations of the country’s flora and fauna, Gay’s Atlas depicts the country’s peoples and customs, including illustrations of tertulias (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 30 and 31), the Mapuche game of chueca (6), and a stark portrait of miners (45).[22] Sagredo observes that the maps and images in the Atlas offer a heterogeneous depiction of the young nation: “Ellas constituyen un notable repertorio de imágenes en las que está representado el Chile de las primeras décadas de la república; tanto en su realidad material natural y cultural, como en la profundidad de las costumbres, mentalidad valores, manifestaciones de piedad y formas de ser colectivas que ellas reflejan” (ix–x).

In the tradition of Gay’s Atlas, Mapa Fílmico offers a multifaceted representation of the Chilean nation through images. Jacob observes that the atlas “needs to be lifted, opened, and leafed through” (67). MAFI embraces the participatory quality of this cartographic genre by inviting viewers to forge their own journeys.[23] Whether it is the depiction of two prostrate religious pilgrims at the Fiesta de la Tirana in the northern region of Tarapacá in Christopher Murray’s Señor, ten piedad (2012) or a class in Concón in which Filipina women learn to cook traditional Chilean food for their jobs as maids in Carlos Reyes’s Basic Kitchen Rules (2015), Mapa Fílmico offers a myriad of ways to see, experience, and think about Chile.

Antonia Girardi underscores the active role of the viewer in navigating the Mapa Fílmico, noting that it is “un espacio múltiple, transitable” (8). Likewise, Josefina Buschmann, the General Editor of MAFI, calls the map a democratic and porous initiative: “el territorio se vuelve líquido a partir de las plataformas web, en el sentido de que uno puede ir desconstruyéndolo y construyéndolo constantemente y eso da una apertura que genera la posibilidad de ir integrando a nuevas personas” (Buschmann “Lo que encuentro” 3-4). Underscoring the fragmentary nature of Mapa Fílmico, Girardi describes the project as “un mapa hecho de retazos” (2). The “plano MAFI” eschews cuts and other editing techniques in favor of a static shot that mirrors the printed images of the traditional atlas, while also drawing attention to the careful composition and structure of the films themselves.[24] Tamara Uribe, a MAFI filmmaker, notes that the static shot foments engagement: “es el espectador quien recorre la imagen, y esa es una exigencia mucho más grande para quien observa” (Buschmann et al. “En conversación” 7). The participatory role of the viewer extends to the process of editing, insomuch as they choose their own journey through the map. MAFI co-founder and filmmaker Christopher Murray describes the Mapa Fílmico as an invitation to openness: “En general los mapas encierran, pero nuestra idea era que éste abriera, que estuviera vivo y fuera inacabable. Un mapa más para perderse que para encontrar” (Bustos 162).

The end credits of Mapa Fílmico films and their arrangement on the Mafi.tv website underscore their cartographic and atlas-like qualities. Each film includes end credits that list— albeit with some variation—the title, a brief summary of the context of the film, the location, the date of shooting, and the director. These credit sequences are analogous to the short descriptions that accompany the images of Gay’s Atlas in that they provide the viewer with contextual information that frames their engagement with the images. The presentation of the films on the Mafi.tv also reflects their close relationship with the traditional atlas. The documentaries are displayed either in the form of a map of Chile with pins indicating the shooting location, or in a grid pattern on a single page. The films are grouped into five color-coded thematic categories: “ecología,” “espectáculo,” “estilo de vida,” “política,” and “tecnología.” Although these categories do not fully encompass the variety of these films, this effort to classify parallels the “encyclopedic” qualities of the atlas (Jacob 67). Additionally, separate pages on the website group documentaries into specials focused on themes like education and the minimum wage. These supplementary thematic groupings highlight the map’s engagement with contemporary political issues, like the 2011 student protests in which thousands of young Chileans took to the streets demanding a better and more equitable education system.[25]

A distinguishing feature of Mapa Fílmico’s representation of early-21st century Chile and which connect it to Gay’s Atlas is its ironic and self-reflexive approach to filmmaking. Three films in particular reflect this sensibility: Hombre fotografiando una bandera gigante (Antonio Luco, 2010), Empanaditas modelo (Pablo Carrera, 2011) and Polo Norte (Bola de cristal) (Maite Alberdi, 2012). [26] Mapa Fílmico establishes its ironic tone and metacinematic portrayal of Chile in Antonio Luco’s Hombre fotografiando una bandera gigante, one of the earliest films by date of shooting.[27] In this short documentary, a man stands holding a camera pointed at a massive Chilean flag opposite La Moneda Palace in downtown Santiago during the celebration of the country’s bicentennial.[28] The film’s title emphasizes the act of filming (“fotografiando”), while also underscoring the grandiose nature of the event (“gigante”). A crowd is visible in the foreground and a band plays martial music offscreen. The frame is bounded by a wall in the lower part of the screen, buildings on the left and right, and five propeller-powered airplanes fly in formation through the top of the frame leaving trails of red, white, and blue smoke—the colors of the Chilean flag—in their wake (00:05-00:17). Shortly thereafter jet planes soar overhead in the same array (00:36-00:41). The photographer below, the large flag above him, and the planes’ smoke trails in the sky bisect the frame. The image of planes soaring over La Moneda Palace on the occasion of the Bicentennial carries a historical resonance, as it evokes the bombing of La Moneda on September 11, 1973 by the country’s Air Force during the coup d’état to overthrow President Salvador Allende. Likewise, the juxtaposition of man, flag, and planes constitute a visual triptych that reflects the motto on the national seal: “Por la razón o la fuerza.” If the man is reason, then the planes are a lavish display of military force and patriotism. However, this unity of reason and force is short-lived. The photographer appears to lose interest after the aircraft pass by, and he exits the frame to the right (00:46-00:48). Rather than embracing “cinema as the mobiliser of the nation’s myths and of the myth of the nation,” this early Mapa Fílmico work exemplifies the idea that cinema should engage critically with these national myths (Hayward 9).

A tone of self-reflexive irony also characterizes Pablo Carrera’s Empanaditas modelo and Maite Alberdi’s Polo Norte (Bola de cristal).[29] In Empanaditas modelo, a photographer, only visible across his midsection, adjusts the position of a cutting of cilantro wedged between empanadas arrayed on a white plate atop a white table in the lower-right corner of the frame (00:04-00:39). The film concludes with the photographer taking a photo of the empanadas (00:40-00:45). A description in the end credits encapsulates what unfolds onscreen: “Sesión fotográfica de empanadas congeladas.” The tableau is replete with irony and metacinematic allusion: the meticulous, larger-than-life intervention by the photographer—whose hand dwarfs the cilantro—reflects the careful way in which the film itself is shot and edited, while the looming presence of the camera highlights the act of filming. Another source of irony is the subject of the film itself. Empanadas are among Chile’s most ubiquitous snacks; however, under the photographer’s hand and the camera’s lens this frozen comestible has been transformed into a healthy and pristine dish, its messy insides and limited nutritional value masked by a sprig of cilantro and its aseptic white surroundings.

Maite Alberdi’s Polo Norte (Bola de cristal) depicts the staging of a traditional Christmas scene inside of a life-sized snow globe within a mall located in a wealthy area of Santiago. The placement of the camera outside of the snow globe positions viewers as critical spectators at a remove from the focal point of the action, while the direct sound from inside the transparent structure aurally immerses spectators inside this Christmas marketing venture-cum-fantasy. This juxtaposition between the image and sound generates an effect of ironic distancing that highlights the humor of staging Santa Claus’s North Pole inside a mall at the beginning of summer in the Southern Hemisphere. People pass in front of the snow globe in the foreground and in the lower-right corner a camera points toward the winter scene. Inside the globe, a man dressed as Santa Claus sits imperiously atop a red sleigh, surrounded by pine trees, a reindeer, and a snowman. The Santa Claus character instructs a young woman in a green elf costume to use a broom to sweep the artificial snow behind the pine trees (00:03-00:42). A man, woman, and baby enter the globe and join Santa on his sleigh. They pose for a photograph taken by a man using the camera in the foreground (00:43-01:28). Like Hombre fotografiando una bandera gigante and Empanaditas modelo, Polo Norte (Bola de cristal) self-reflexively draws attention to the act of filmmaking itself through its representation of the staging and photographing of a meticulously constructed artifice. The self-reflexive qualities of these three films recall the lithograph from Gay’s Atlas, Visita al volcan d’Antuco al momento de una erupcion de gaz (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 36), composed by Gay and Pedro Federico Lehnert. The image features the date March 1, 1839 and depicts the French naturalist walking unperturbed inside the volcano’s crater as it erupts (Sagredo Baeza xlvii-xlviii). Next to Gay, others flee for their lives. The viewer witnesses the event from an elevated point of view and looks down into a choreographed and dramatic representation of a natural phenomenon. Gay’s meta-image foregrounds its creator and presents the artist and naturalist as collected and courageous in the face of danger.[30]

Carreras de caballos

In addition to their self-reflexive qualities, both Mapa Fílmico and Gay’s Atlas share a focus on Chilean social traditions and the country’s socioeconomic stratification. Mapa Fílmico documentaries depict a variety of social practices across socioeconomic classes. These range from clients getting a haircut at a Dominican barbershop in a working-class neighborhood of Santiago in Christopher Murray’s Peluquería Dominicana (2012), to visit by a group of boys to a Johnny Rockets soda fountain in a wealthy Santiago suburb in Valeria Hofmann’s American Dream (2013), to drag queens getting dressed backstage for a show in Daniela Camino’s Yo soy drag queen (2013). Together, these socially-focused films present Chile as a vibrant and diverse place, where ethnicity, wealth, and gender identity shape social practices.

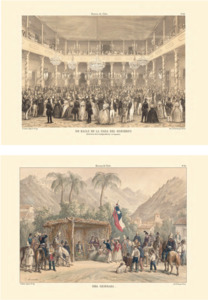

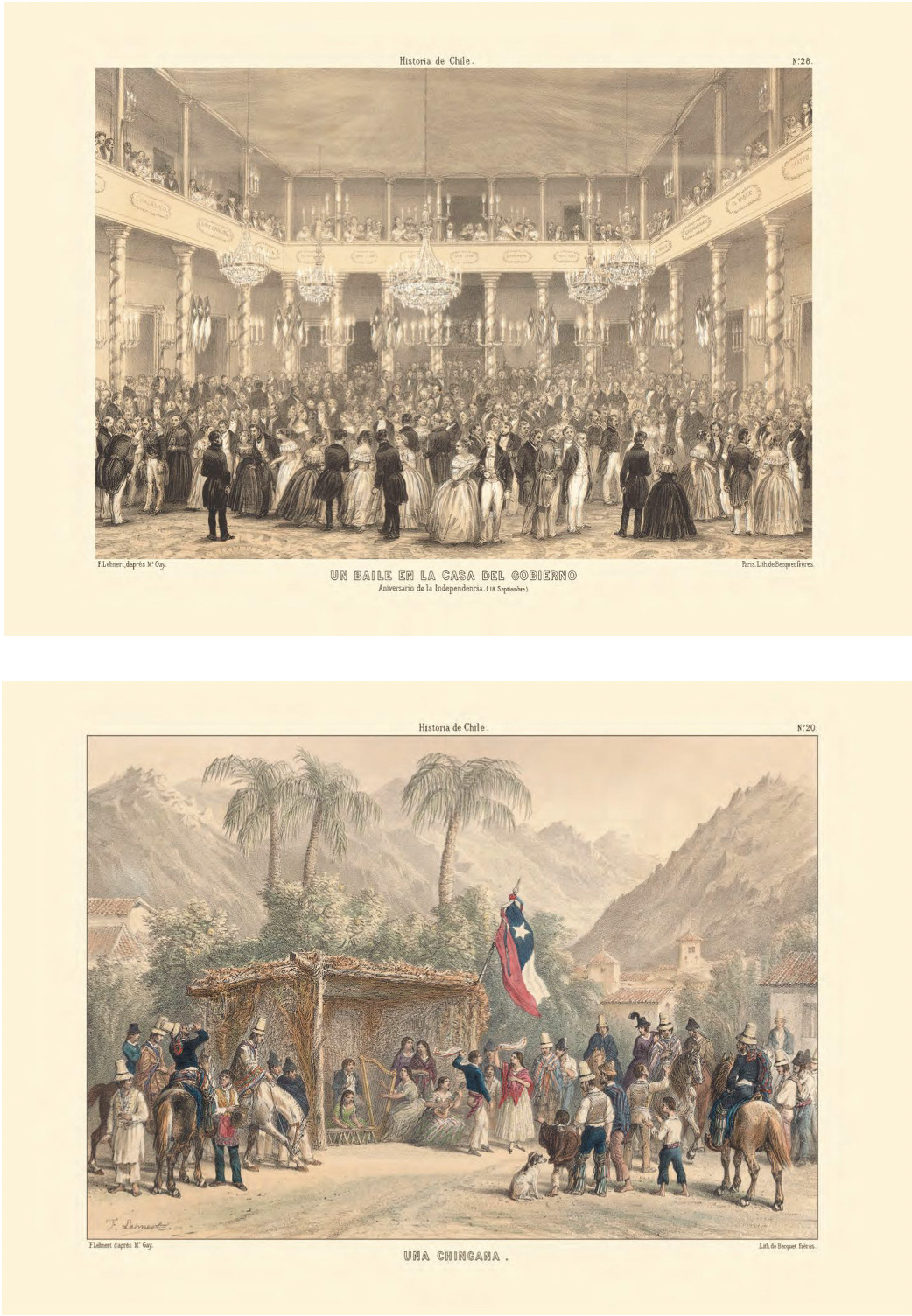

Gay’s Atlas also highlights the social practices of Chileans across social strata. Two adjacent illustrations by Gay and Lehnert exemplify the Atlas’s representation of a broad swathe of Chilean society. The first of these, Un baile en la Casa del Gobierno, (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 28), shows a formal ball underway in a spacious and well-appointed hall on the occasion of the Independence Day celebrations on September 18. Men dressed in tails dance with women in elegant gowns beneath crystal chandeliers. The subsequent image features a less glamorous tradition with rural roots. Una chingana (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 29) shows an open-air, straw-thatched shack amid a mountainous valley. Inside the small edifice a group of female musicians perform to a group of revelers situated outside who dance the cueca and imbibe beneath a Chilean flag. The historian Brian Loveman describes the chingana as a redoubt of the lower classes, “a combination of bar, dance hall, and brothel” (103). In the first volume of Agricultura (1862) of his Historia, Gay depicts the chingana as a source of vice for campesinos, “En las cercanías de Santiago, etc., el trabajo es más continuo, pero el sábado, que es el día de pago, pasan su tiempo en las chinganas o en el juego y todo lo que han ganado en la semana desaparece a veces en algunas horas” (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 103). Gay’s illustration Una chingana represents a (morally dubious) microcosm of the Chilean nation. It is a space of social mixing where huasos, landowners, and campesinos revel together under open skies and the national flag.[31]

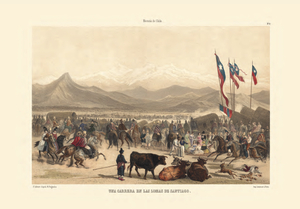

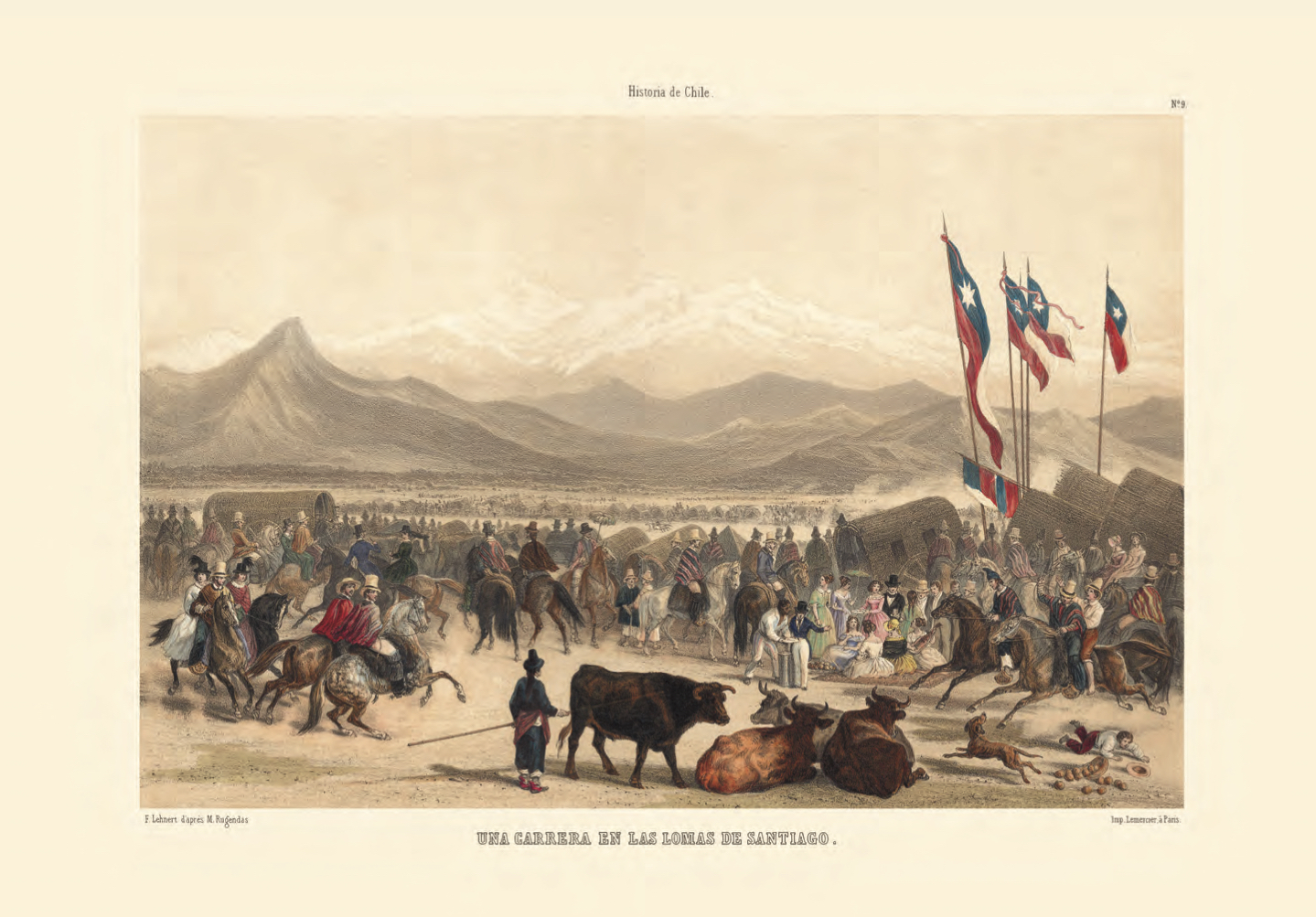

Horseracing is a sport and social pursuit with deep roots in Chile. Loveman notes that horseracing was one of the favorite activities of the Chilean lower classes in the early-19th century (103). Gay examines this popular pastime in both his Atlas and Historia. He depicts the sport as a fundamental part of rural life and the country’s national identity. In the first volume of Agricultura (1862) of his Historia, Gay writes that the greatest “regocijos” of the campesino are “las carreras de caballos, las peleas de gallos, su juego de bolas y las fiestas religiosas, a las cuales son muy adictos” (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 115). The naturalist goes on to describe a horserace in vivid terms: “Luchan caballo contra caballo y por el cuello y el pescuezo, lo que se llama pechear, hasta que uno de los dos cede a impulsos del otro: cogidos dos jinetes a una sola correa corren juntos hasta que uno queda vencido, y algunas veces recogen del suelo a la carrera objetos de poco volumen” (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 270, author’s emphasis). Gay’s Atlas includes a polychrome lithograph of a horserace in Santiago titled Una carrera en las lomas de Santiago by Juan Mauricio Rugendas and Pedro Federico Lehnert that captures the thrill of this pastime and its close association with national identity (Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile 9). In the foreground, a group of people, including an afro-Chilean, gentry, huasos, and campesinos—identifiable by their dress—race horses, tend cattle, and converse beneath four Chilean flags flying overhead. The Andes mountains loom in the background, their grey tones contrasting with the colorful figures below. The image represents this race as a scene of national unity, bringing together a motely group of spectators from across social classes and ethnicities amid a bucolic Central Valley landscape.

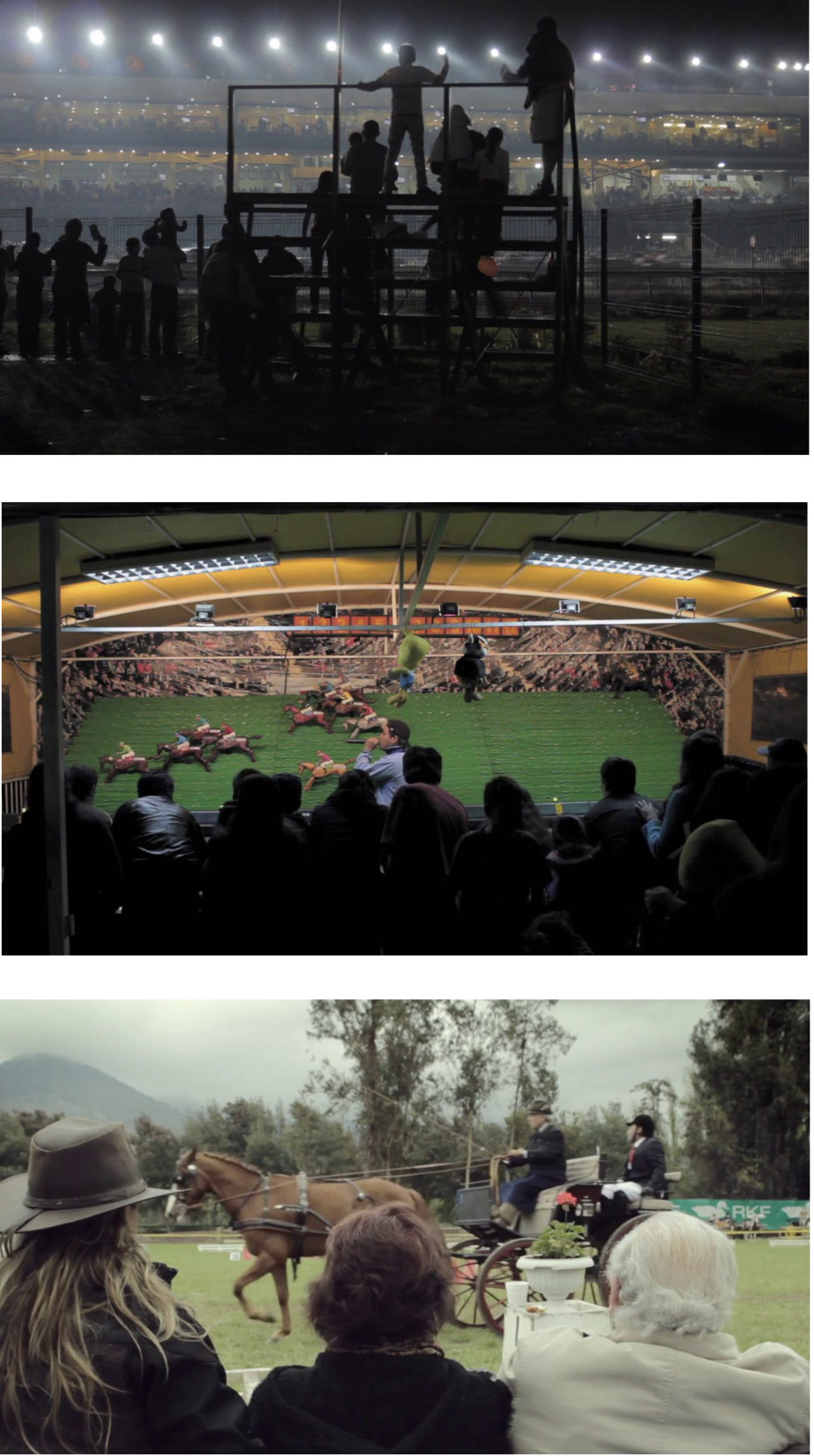

A trio of MAFI films centered on the sport of horseracing share a close connection to both Gay’s representation of the pastime in his Atlas and Historia. Antonio Luco’s Octava carrera (2011), Christopher Murray’s Carrera de caballos pequeños (2011), and Daniela Camino’s Vida social: campeonato de carrozas (2012) illustrate horseracing’s appeal in 21st-century Chile, while echoing the self-reflexive sensibility of Gay’s Atlas. Like Una carrera en las lomas de Santiago, these three Mapa Fílmico films depict horseracing as a leisure activity that appeals to Chileans across social classes. However, rather than presenting horseracing as a unifying pursuit as Gay does, these films present the sport as a reflection of the country’s social divisions and high levels of socioeconomic inequality.[32]

Antonio Luco’s Octava carrera depicts a horse race in Santiago’s Hippodrome from the vantage point of an audience on the outskirts of the track.[33] The camera is positioned behind a set of bleachers on and around which a group of a dozen or so people sit and stand, their backs to the camera as they watch the race. From this dark corner of the track, the spectators are silhouetted against the bright stadium lights arrayed horizontally across the top of the frame. In front of this group of onlookers lies the dirt track of the Hippodrome. A man’s voice offers commentary over the stadium’s loudspeakers and the audiences’ cheers grow louder as the race progresses. The climax occurs as the horses briefly hurtle through the frame (00:44-1:03). Unlike the spectators in the well-lit box seats in the background, the onlookers in the foreground are shrouded in darkness, an effect which underscores their marginalized position. As is the case with the other two Mapa Fílmico documentaries that depict horseracing, Octava carrera places spectators at its center formally and thematically. The film emphasizes the crowd’s passion, camaraderie, and solidarity as they watch the eighth race of the evening.

In addition to representing the broad appeal of horseracing, Christopher Murray’s Carrera de caballos pequeños exemplifies the ironic and participatory nature of Mapa Fílmico.[34] The film opens in medias res as a horseracing-themed game of galoppen unfolds at an amusement park. Players compete in skeet ball to move horse figurines arrayed against the wall. An audience silhouetted against the bright lights illuminating the race looks on in the foreground (00:00-00:44). In between the players and the horses, a man with a microphone provides running commentary. After the race ends, the crowd disperses (00:45-00:54). As in Octava carrera, the camera offers a wide-shot perspective from behind the crowd. The setting for the film is Fantasilandia, an amusement park founded in 1978 in Santiago’s Parque O’Higgins. A jingle from a 1985 commercial for the park distills its appeal: “Fantasilandia, ilusión y realidad” (“Comercial Fantasilandia”). In depicting a simulacrum of horseracing, Murray’s film plays with the interplay between illusion and reality, in which this traditionally rural activity is transformed into a carnival-style game for urbanites. The “caballos pequeños” of the tongue-in-cheek title are toy miniatures, but the excitement around the race is real. This version of horseracing requires the participation of its players—a dynamic which mirrors the role of the Mapa Fílmico spectator. Whereas in Octava carrera the dim-lighting of the audience reflects their marginality, here it underscores the crowd’s fluidity and the egalitarian nature of the game.

Whereas Octava carrera and Carrera de caballos pequeños present horseracing’s popular appeal, Daniela Camino’s Vida social: campeonato de carrozas represents the sport as an activity of the upper classes. The documentary depicts two women and a man in the foreground, looking out over a grass arena where horses towing carriages pass in and out of the frame beneath mountains shrouded in fog. As the title suggests, the horses and drivers are taking part in a combined driving race event.[35] In a 2015 article in Equestrian Magazine, Kathleen Landwehr underscores the bourgeois appeal of combined driving: “Driving is a fascinating equestrian sport to watch, steeped in tradition and decorum” (33). Camino’s film links this niche equestrian sport to wealth, privilege, and high society gossip—a point underscored by the first part of the film’s title. The camera is positioned closely behind the group of three onlookers who turn their heads in unison to follow a horse and carriage as they pass in front of them. The camera and microphone’s intimate positioning among the spectators accentuates this elite social environment. Viewers overhear a conversation between a man and a woman (neither of whom are visible in the frame) over the sound of the repeated clicks of a camera shutter. The off-screen pair discuss their friend Lola, who recently traveled to Paris and appeared in a photo with Yves Carcelle, the former chairman and CEO of the luxury goods company Louis Vuitton (00:29-00:49). A camera shutter coincides with the cut to the end credits, drawing attention to the act of filming as well as the see-and-be-seen nature of the gathering (00:49).

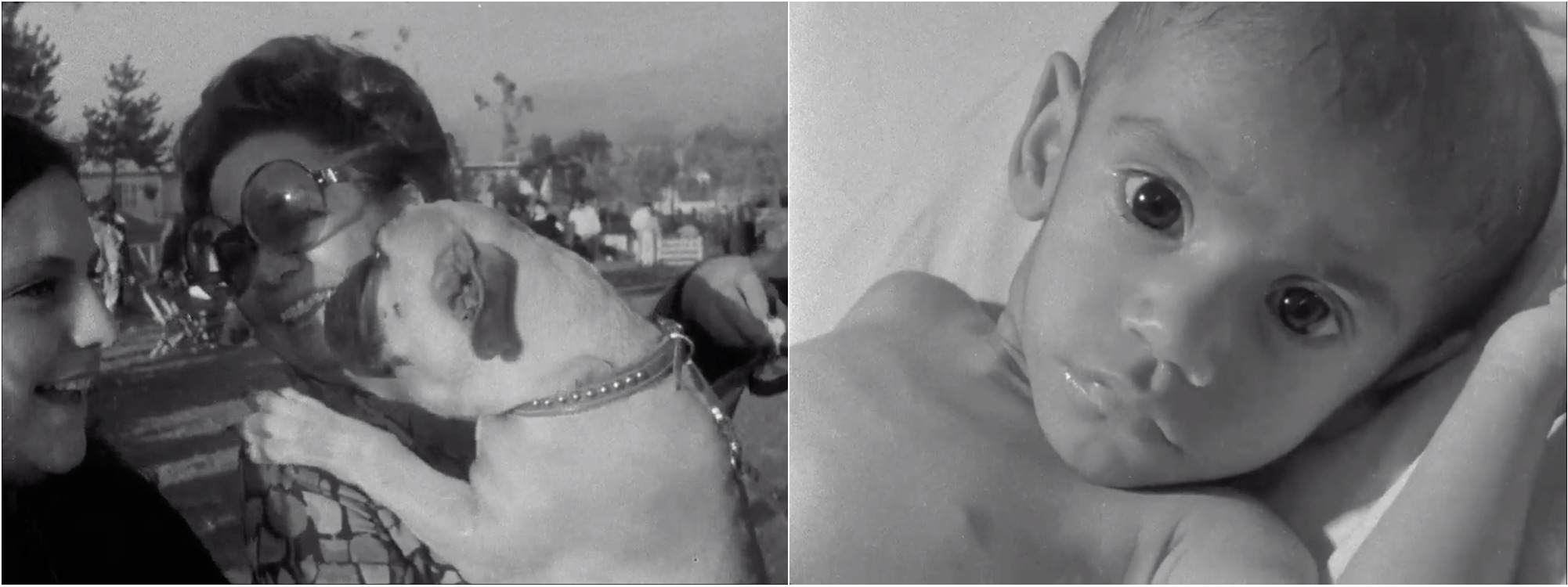

Camino’s film evokes the memorable dog show sequence in Pedro Chaskel and Héctor Ríos’s short documentary Venceremos (1970), produced by the Centro de Cine Experimental. The open-air canine pageant depicted in the film is attended by a wealthy audience, which watches from the stands as fastidiously groomed dogs are paraded before them. A series of close-ups shows onlookers yawning and looking bored. The sequence is coupled with the non-diegetic music of Cesare Bixio’s operatic “Vivere,” which ironically emphasizes the frivolity of the event amid the politically tumultuous period following Salvador Allende’s confirmation to the Presidency by Congress in October 1970.[36] The film condemns this decadent parade of dogs and their well-heeled owners and through its use of editing: the sequence is bookended by images of a malnourished children. Regarding this juxtaposition of socioeconomic extremes, Manfred Engelbert observes: “La única conclusión que admiten las imágenes filmadas de una competencia de animales mimados al máximo es que los perros, en este ‘mondo cane’, parecen obtener más atención que los niños” (23). A similar, albeit less severe, juxtaposition occurs with Vida social in relationship to the other two MAFI horseracing-themed films. Whereas Octava carrera shows horseracing as an activity that draws a marginalized audience and Carrera de caballos pequeños utilizes irony to depict a game of horseracing as a popular attraction, Vida social represents horseracing as an elite and insular pursuit.

Mapa Fílmico de un País offers a participatory and multifaceted portrait of post-Transition to Democracy Chile. At its core, Mapa Fílmico is a collaborative project that incorporates the work of dozens of filmmakers, whose distinct visions shape the collection’s kaleidoscopic representation of the country and its peoples. Like its predecessor, Gay’s 19th-century Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile, this cinematographic atlas demands active viewers who make connections across its component parts and trace their own itinerary through the country, be it via a visit to a mall-bound Santa Claus or the horseracing game galoppen at an amusement park. Both the French naturalist’s Atlas and Mapa Fílmico share a self-reflexive sensibility, which invite viewers to consider the role images play in our conceptions of the nation, be it an illustration of a fearless Gay standing atop a volcano crater or the staging of a photoshoot for an empanada. And, similar to Gay’s Atlas, Mapa Fílmico depicts the country’s social practices and socioeconomic stratification, most notably in its representation of horseracing as a quintessential Chilean pastime and a mirror onto the country’s deep-seated inequality.

As a means of conclusion, I want to highlight one film which exemplifies the collection’s ethos of active viewership, collaboration, self-reflexivity, and plural representation of Chile. Juan Francisco González’s Idioma local (2016) is set in a classroom in Quilicura in the Santiago Metropolitan Region where group of adult Haitian students are learning Spanish.[37] The students sit arrayed in rows of seats facing a teacher, who is offscreen. The teacher presents a brief lesson on the words “abuelo” and “abuela”, who she defines as the “los padres de mis papá” (00:07-00:13). The students appear lost, so the teacher methodically describes the relationship between herself, her parents, and her grandparents. With her pupils now grasping the lesson, the teacher asks them how to say abuelo in Haitian Creole. In response, the students shout out “grandpè” and “granpapa” (00:40-00:53). With its focus on these Haitian immigrant students, the film brings the country’s racial and ethnic diversity to the forefront. And in showing this Spanish class, the film invites viewers to engage with the experiences of immigrants striving to incorporate themselves more fully into Chilean society. Moreover, consistent with Mapa Fílmico’s self-reflexive and ironic sensibility, the film reverses the traditional classroom dynamic by placing the students at its center and ending with the erstwhile pupils presenting their teacher a lesson in their “local” language, Haitian Creole. Like this language classroom, with its goal of constructing bridges to mutual understanding, Mapa Fílmico de un País asks viewers to take a little bit of time to explore Chile with an open mind and an ever-curious eye.

Filmography and Technical Summary: Mapa Fílmico de un País

American Dream

Direction: Valeria Hoffman

Production: Catalina Alarcón

Date of Shooting: May 2013

Running Time: 1’27"

Location: Restaurant Johnny Rockets, La Dehesa, Santiago

URL: http://mafi.tv/american-dream/

Basic Kitchen Rules

Direction: Carlos Reyes

Sound: Catalina Monzalvett

Date of Shooting: March 2015

Running Time: 1’16”

Location: Agencia de nanas filipinas, Concón, Región de Valparaíso

URL: http://mafi.tv/basic-kitchen-rules/

Carrera de caballos pequeños

Direction: Christopher Murray

Editing: Tamara Uribe

Production: Paulina Sanhueza

Date of Shooting: June 2011

Running Time: 1’00"

Location: Fantasilandia, Santiago

URL: http://mafi.tv/carrera-de-caballos-pequenos/

Empanaditas modelo

Direction: Pablo Carrera

Production: Paulina Sanhueza

Date of Shooting: June 2011

Running Time: 0’52"

Location: Providencia, Santiago

Occasion: Sesión fotográfica de empanadas congeladas

URL: http://mafi.tv/empaditas-modelo/

Hombre fotografiando una bandera gigante

Direction: Antonio Luco

Date of Shooting: September 2010

Running Time: 1’01"

Location: La Moneda, Santiago

Occasion: Conmemoración del Bicentenario

URL: http://mafi.tv/hombre-fotografiando-una-bandera-gigante-2/

Idioma local

Direction: Juan Francisco González

Editing: Isabella Jacob

Sound: Romualdo Castro

Production: Catalina Alarcón

Date of Shooting: August 2016

Running Time: 0’59"

Location: Quilicura, Santiago

Occasion: Clase de español para haitianos

URL: http://mafi.tv/idioma-local/

Octava carrera

Direction: Antonio Luco

Date of Shooting: July 2011

Running Time: 1’03"

Location: Hipódromo Chile, Santiago

URL: http://mafi.tv/octava-carrera/

Peluquería Dominicana

Direction: Christopher Murray

Production: Carlos Collío

Date of Shooting: August 2012

Running Time: 0’55"

Location: Persa Bío Bío, Santiago

URL: http://mafi.tv/peluqueria-dominicana

Polo Norte (Bola de cristal)

Direction: Maite Alberdi

Sound: Carlos Collío

Production: Jeremy Hatcher

Date of Shooting: December 2012

Running Time: 1’37"

Location: Mall Parque Arauco, Santiago

URL: http://mafi.tv/polo-norte/

Señor, ten piedad

Direction: Christopher Murray

Production: Paulina Sanhueza

Date of Shooting: June 2012

Running Time: 1’13"

Location: Pozo Almonte, Región de Tarapacá

URL: http://mafi.tv/senor-ten-piedad/

Vida social: campeonato de carrozas

Direction: Daniela Camino

Date of Shooting: February 2012

Running Time: 0’59"

Location: Pirque, Santiago

Occasion: Primer Campeonato de Enganche Ecuestre

URL: http://mafi.tv/vida-social-campeonato-de-carrozas/

Yo soy drag queen

Direction: Daniela Camino

Camera: Valeria Hofmann

Production: Catalina Alarcón

Date of Shooting: March 2013

Running Time: 1’11"

Location: Bunker Discotheque, Santiago

URL: http://mafi.tv/yo-soy-drag-queen/

As of April 2020, 262 documentaries, were streaming on the main page of Mafi.tv. Additional documentaries produced as part of the Escuela MAFI workshops were available on separate pages. 65 filmmakers have directed or co-directed works for Mapa Fílmico on MAFI.tv (this number excludes those directors only credited for Escuela MAFI films).

Chile’s Transition to Democracy begins with the 1988 plebiscite and ends with a series of constitutional reforms implemented by President Ricardo Lagos in 2005 that restored full civilian control over the military. See Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, “Reforma constitucional que introduce diversas modificaciones a la constitución política de la República”, and The Economist, “Chile: Democratic at Last”.I will refer to the umbrella not-for-profit Fundación MAFI organization as “MAFI” and the map of short documentaries as “Mapa Fílmico.”

The formal constraints of Mapa Fílmico have parallels in “The Vow of Chastity” (1995) manifesto published by the Dogme 95 filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, most notably as it relates to the exclusive use of diegetic sound.

MAFI posts Mapa Fílmico films on Facebook (facebook.com/MAFI.tv), Instagram (instagram.com/mafi_tv/), Twitter (twitter.com/mafi_tv), and Vimeo (vimeo.com/mafitv).

Grierson travelled to Chile in June 1958. During his visit he met with Sergio Bravo and other members of the Centro de Cine Experimental. See Bravo, “Cincuenta años ya . . .”

These longer-form documentaries are Propaganda (2014), which depicts the 2013 Presidential campaign; Pampas marcianas (2018) which was produced as part of a residency program and shot in collaboration with the inhabitants of the town of María Elena in the Atacama Desert; and Dios (2019), which focuses on Pope Francis’s 2018 visit to Chile.

According to the 2017 national census, Chile’s population measured 17.6 million people, with 7.1 million people or 40.5% of the population residing in the Santiago Metropolitan Region. Chile is a highly urbanized country. In 2017, 87.8 percent of the population resided in urban areas. See Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (5–6).

The creation of MAFI was supported by a grant from the Fondo de Fomento Audiovisual in 2011. Established in 2004, the Fondo de Fomento Audiovisual is the Chilean government’s primary mechanism for supporting cinema. It is run under the auspices of the Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio, which replaced the Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes (CNCA) in 2017. Additional support for Mapa Fílmico documentaries has come from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, the Festival Internacional de Cortometrajes de Talca, and the Festival Internacional de Cine de Iquique.

In May 2017, MAFI hosted two Escuela MAFI programs in Mexico in conjunction with the not-for-profit Ambulante organization. In 2017, MAFI also collaborated with the Santiago-based Museo de la Memoria’s “Mala Memoria” competition, in which filmmakers submitted microdocumentaries on the themes of “la memoria, la solidaridad y la importancia de los derechos humanos” (“Mala Memoria III”). The filmmakers of the twenty selected films were invited to participate in a MAFI workshop.

In 2015, MAFI received a grant from the CNCA to expand its Escuela MAFI program. See Galaxia UP, “Escuela MAFI, una instancia de aprendizaje para detenerse y observar” and Lagos Labbé (172-78).

The collaborative films Melipeuco: una película hecha por todos (Aníbal Jofré, 2016) and Como un ventarrón fílmico (Aníbal Jofré, 2019) were produced with financing from the state-sponsored Programa Red Cultura.

The article was published under Mistral’s given name Lucila Godoy Alcayaga. She argues that this institute “podrá hacer en nuestro favor lo que no ha realizado institución europea alguna, en el sentido de excitar a las empresas a la divulgación gráfica de nuestro continente; en el de articular los trabajos ya logrados y darles unidad, y en el de purificar, con el solo incremento del cine geográfico e histórico de índole documental, la plaga del cine imbécil o perverso que anega nuestros mercados. No necesitará para lo último combatir a ninguna empresa explícitamente; bastará con que informe a los pueblos de América respecto del material disponible de películas con asunto nuestro, con panorama, costumbres e historia nuestras. Los pueblos ibero-americanos harán la selección por sí mismos” (467-68). For an analysis of the connection between MAFI and Mistral see Girardi (8-9).

Colectivo Registro Callejero includes some MAFI contributors and members of the Asociación de Productores Independientes.

Jorge Iturriaga and Iván Pinto point to the central role of digital and new-media filmmaking collectives like Colectivo Registro Callejero during and in the aftermath of the wave of protests in late 2019. See Iturriaga and Pinto, “Hacia una imagen-evento. El ‘estallido social’ visto por seis colectivos audiovisuales (Chile, octubre 2019).” For more on the origins of the 2019 protests see Amanda Taub, “‘Chile Woke Up’: Dictatorship’s Legacy of Inequality Triggers Mass Protests.”For more examples of contemporary digital documentary filmmaking in the Spanish-speaking world, see Cerdán and Fernández Labayen, “The cartographic imagination in Spanish and Latin American documentaries: technological, social and physical mapping across the Hispanic Atlantic.”

The extant fragments of Giambastiani’s film were restored by filmmakers Patricio Kaulen and Andrés Martorell and released in 1957 under the title Recuerdos del Mineral “El Teniente”.

Cortínez and Engelbert describe the Centro de Cine Experimental as the place where “se concentran los esfuerzos para la creación de un cine chileno de arte” (84). The Centro was founded by Sergio Bravo in 1957. In June 1963, Chaskel replaced Bravo as leader of the Center and the institution was incorporated into the University of Chile as the Sección Cine Experimental within the Departamento Audiovisual. In 1977, Bravo revived the Centro, which produced his film No eran nadie (1979) and staged the inaugural Film Festival of Mapuche Cinema (KIÑE TRAWUN KINE MAPUCHE) in 2000.

Guzmán’s documentary is a personal reflection on his relationship with Chile, the 1973 coup, and the Cordillera de los Andes. It is the final part of his trilogy of films—Nostalgia de la luz (2010) and El botón de nácar (2015) are the first two entries— centered on memory, the golpe de estado, and post-Transition to Democracy Chile.

Gay was known by the first name Claudio in Chile. His given name was Claude.

Gay’s Historia is comprised of eight volumes on history, eight on botany, eight on zoology, two on agriculture, two volumes of documents.

For more on Portales and the Portalian state see Brian Loveman, Chile: The Legacy of Hispanic Capitalism (109-13).

Rafael Sagredo Baeza highlights the significance of these maps within the Atlas: “Su sola existencia, además de facilitar la historia de la cartografía nacional y enseñar acerca de la conformación política y administrativa de la joven república, muestra la transcendencia que el Estado de la época le asignó a la información geográfica y el valor que Gay le atribuyó para la comprensión de su trabajo” (lxiv).

Sagredo Baeza singles out the portrait of the two miners as an example of Gay’s self-awareness and his understanding of the country’s social realities: “De manera indirecta, pero fiel a la realidad, tras el primer plano de los dos mineros, aparecen las etapas de su quehacer, reproduciéndose las extremas condiciones en que se realizaba. Un ejemplo más del poder de observación del científico, pero también de su plena conciencia respecto del carácter de su obra gráfica y de la ‘sensibilidad’ de su público en Chile. Como es obvio, Gay no quiso ‘ofender’ a la elite nacional, pero tampoco obviar las que creía eran realidades indispensables de mostrar” (lii). The early Chilean documentary filmmaker Salvador Giambastiani offers a similarly unvarnished portrait of mining in El Mineral El Teniente (1919).

The number in parentheses denote the number of the image in Gay’s Atlas.Tom Conley describes the presence of a map in a film as “a point of departure for an interpretive itinerary” (208).

The MAFI logo features a tripod in lieu of an “A,” in a nod to the centrality of the static shot in the organization’s films.

For more on the student movement see Barrionuevo, “With Kiss-Ins and Dances, Young Chileans Push for Reform.”

The date in parentheses after the title of these short documentaries refers to their date of shooting.

Antonio Luco is the co-director of the feature-length documentary Los castores (2014).

This megabandera measures 18 by 27 meters. See El Mercurio, “Presidente Piñera encabeza izamiento de la gran bandera del Bicentenario”. Although Chile formally attained independence in 1818, the country claims September 18, 1810 as its Independence Day. On that date, a national junta assumed control of the country in the aftermath of the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1807. The junta swore allegiance to the deposed King Ferdinand VII of Spain. See Loveman (100-01).

Pablo Carrera is the director of the feature-length fiction film Manuel de Ribera (2010). Maite Alberdi is the director of the feature-length documentaries El salvavidas (2011), La Once (2014), Los niños (2016), and El agente topo (2020).

Sagredo Baeza draws connections between Gay’s representation of his ascent of the Antuco Volcano and the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s illustrations of Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador: “La actitud del científico de representarse al interior de las figuras, convirtiéndose así en protagonista de su propia obra, tiene su antecedente más inmediato en las vistas que Alexander von Humboldt había publicado luego de su viaje americano. Desde entonces se transformó en un gesto propio de los naturalistas y artistas viajeros. La emoción del contacto y comunión íntima con la naturaleza, el afán de dar un tono de ‘reportaje’ a los textos e ilustraciones, tanto como la urgencia de mostrar la calidad de científico o pintor en terreno, explicarían esta actitud. En el caso de la estampa en que aparece Claudio Gay en el cráter del Antuco está también el afán por exhibir los lejanos lugares que exploró, los riesgos a que se expuso en su afán por dar a conocer Chile y, además, mostrar que él, al igual como había presumido Humboldt después de escalar el Chimborazo, también había alcanzado la cima de una cumbre andina, en este caso un volcán; lo que sumaba otro motivo de curiosidad y atracción provocado por la obra del sabio prusiano” (xlviii).

Loveman describes the huaso as an archetypal Chilean figure with profound cultural significance: “The huaso is the Chilean cowboy but connotes much more. The flesh and blood huaso is a campesino on horseback or in the fields, who, before the 1970s, worked from sunup to sundown, frequently barefoot or in crude sandals called ojotas, and wearing an apron or a flour sack around his waist. When not at work he sported a jacket inherited from his father or older brother and a well-worn hat. There is also the tourist’s huaso, dressed for the rodeo in a three-colored manta and a sash around his waist (red, white, and blue like the Chilean flag). He rides a strong, well-kept horse which he prods with silver spurs. This was the hacendado, or his hireling, dressed in his best huaso outfit to visit the countryside at the harvest or to make sure the campesinos attend to their labors. The first huaso, the rural worker, bears the brunt of hundreds of country bumpkin jokes. The latter, the postcard huaso, typifies the historic rural basis of the wealth and power of many of Chile’s leading families. Together, they are the story of Chile—a national symbol which denotes hard work, sacrifice, and struggle to the campesino, and power, leisure, and privilege to the hacendado” (52, author’s emphasis).

According to the OECD, Chile’s Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, measured .471 in 2011 and .460 in 2017. For comparison, the United States’ Gini coefficient measured .396 in 2013 and .390 in 2017 (OECD, Income Inequality). In 2014, the share of total net wealth owned by the wealthiest ten percent of households in Chile measured 57.1 percent, compared to 8.49 percent of total net wealth owned by the bottom sixty percent of households (OECD, Wealth: By Country).

The position of the camera and the spectators evokes the sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956) in which Nikki Arcane (Timothy Carey) shoots a horse from his convertible parked at the far edge of the track.

Christopher Murray is the co-director of Manuel de Ribera (2010), the director of the feature-length fiction film Cristo ciego (2016), and the co-director of the MAFI documentary Dios.

In combined driving, a horse or team of horses pull a carriage while competing in a triathlon style series of events: dressage, marathon, and a timed obstacle course. In 1970 combined driving was incorporated as an official sport of the Fédération Équestre Internationale. See United States Equestrian Federation, “Combined Driving”

Manfred Engelbert writes that the film is a celebration of the possibilities and hope of the new Allende government: "Se hace — según Chaskel — en el contexto del secuestro y el asesinato del general René Schneider y después de la confirmación de Allende por el Congreso en octubre de 1970, para apoyar al gobierno de la Unidad Popular contra las acciones agresivas de la derecha. Pero si la película se mira con atención se descubre que ésta no es la expresión de un programa político. […] La película es más bien la expresión de la enorme esperanza colectiva de poder terminar con una sociedad injusta y alienante (20).

An estimated 179,000 Haitians were living in Chile in 2019 (INE, 21). For more on Haitian immigrants in Chile see Jacqueline Charles, “Haitians gamble on a better life in Chile. But the odds aren’t always in their favor.”