1. Introduction

The field of Spanish heritage language (SHL) teaching and learning, starting with the seminal works of Guadalupe Valdés in the 1970s, has been driven largely by a twofold objective. The first one is to understand at a deeper level who SHL learners[1] are and what makes them different in terms of their diverse linguistic experiences and backgrounds, goals and motivations, interests, and attitudes. The second objective is to determine which instructional practices may be the most beneficial to effectively address said unique profiles (e.g., Beaudrie et al., 2014; Beaudrie & Fairclough, 2012; Pascual y Cabo, 2016; Potowski, 2018; and more). Currently, there is a general underlying agreement that a combination of sociolinguistic approaches to HL instruction, critical language awareness, critical pedagogy, ecological orientations, and flexible language practices constitute and define state-of-the-art of SHL teaching. While these courses tend to have a strong focus on language (i.e., grammar, orthography, etc.), there is also emphasis on SHL learners themselves, and their relationship with the HL (e.g., Beaudrie et al., 2014; Wilson & Pascual y Cabo, 2019).

To date, the overall evidence available seems to overwhelmingly indicate that following these theoretical and philosophical approaches yields positive effects on the student’s identity, self-esteem, sense of belonging, and even academic performance all around (e.g., Carreira, 2016; Parra, 2016; Valdés & Parra, 2018). That said, one important question that is at the heart of current SHL education research initiatives is the extent to which said practices are actually effective for our students’ linguistic and bi/multiliteracy development. In other words, what kind of language and literacy learning/development does SHL instruction afford our students? how much can they be expected to learn as a result of SHL instruction? To be sure, there is already a significant body of work that has attempted to answer these questions (e.g., Colombi, 2002; Elola & Mikulski, 2016; Potowski et al., 2009; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018). And although their research goals were in many ways similar to ours, as we will discuss in detail later, their methods and procedures differ significantly. For one, they tested students who either received explicit intervention instruction, were allowed to plan, review and edit their work, and/or were allowed to use outside sources when completing the tasks (e.g., Colombi, 2002; Elola & Mikulski, 2016; Potowski et al., 2009; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018). Considering this, in this study we seek to address an equally pertinent and relevant contribution: whether the findings reported in the abovementioned studies can be replicated or at least approximated to some degree when the students do not receive explicit intervention instruction or do not have the time or opportunity to revise their work. Specifically, we attempt to achieve this goal by identifying whether and the ways in which SHL instruction contributes to improvements in students’ academic writing skills, which include, but are not limited to, written conventions of the language, lexical density, and structural complexity (e.g., Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018).

This goal resonates with and is informed by recent calls to further examine the relationship between SHL teaching and language acquisition.

2. Outcomes of Spanish Heritage Language Instruction

Although admittedly an underdeveloped area of study, Bowles (2018) and Bowles and Torres (forthcoming) reckon with how traditional explicit grammar instruction is generally argued to be beneficial in terms of language acquisition (e.g., Bylund & Díaz, 2012, 2012; Colombi, 2002; Montrul & Bowles, 2009; Potowski et al., 2009). Though not conclusive, the evidence available is supportive of the view that explicit instruction can facilitate SHL acquisition. For example, Potowski et al. (2009) compared the effects of both, implicit and explicit instruction on the acquisition of the Spanish imperfect subjunctive among L2 and HL learners. Participants were randomly assigned to processing instruction (PI) or Traditional Instruction (TI) treatment. Their results showed that, while both types of instruction were beneficial, L2 learners seemed to benefit the most from explicit language instruction. Relatedly, in order to further investigate what specialized types of instruction may be most beneficial for HL development, Montrul and Bowles (2010) studied the effects of explicit instruction on the acquisition of the differential object marking and gustar- type verbs. Their findings also showed significant gains as a result of explicit grammar instruction. Likewise, Bylund and Diaz (2012) examined the effects of Spanish HL instruction in the context of Sweden.

The HSs that participated in this study were divided into two groups, depending on whether they were enrolled in a SHL class or not. Consistent with Potowski et al. (2009), and Montrul and Bowles (2010), their findings also showed that students who were attending HL classes achieved higher scores on a grammaticality judgment task and a cloze test examining a number of morphosyntactic and semantic properties.

Along the lines of these studies, Parra et al., (2018) investigated the quantitative and qualitative changes in the oral narratives of SHL learners enrolled in a fifteen-week-long course. The study adopted a pre and post-test design and the analysis included several categories such as the use of discourse connectors, tenses, and lexical proficiency. Their results showed that students made favorable improvements in all the aforementioned areas, and we take these results to claim that a combination of pedagogical practices such as a rich language classroom environment that fosters meaningful interaction, scaffolding, and explicit instruction will inevitably benefit SHL learners.

In sum, despite these important advances, additional research is clearly needed. The current study joins this general endeavor to further increase our understanding of the full reach and impact of SHL instructional benefits. Herein, we seek to explore whether, and to what extent, SHL instruction can contribute to improvements in HSs’ overall literacy skills. Specifically, we are interested in examining changes in students’ writing performance in terms of lexical density (LD, henceforth), overall grammatical intricacy (GI, henceforth), and the use of phonographic-alphabetic conventions of the written language (i.e., spelling).

The premise of the present study is as follows: from previous SHL literature, we know that HSs not only tend to exhibit stronger oral (i.e., speaking and listening) than writing skills (i.e., reading and writing) but, in fact, that orality seems to be one of the defining features of their writing production (e.g., colloquial vocabulary or phonetically influenced spelling). These orality features are often interpreted as the absence of literacy (e.g., Benmamoun et al., 2013; Carreira, 2016; Montrul, 2016; Potowski, 2018). With this in mind, we seek to explore whether, after one semester of SHL instruction, learners’ overall writing performances show signs of development away from orality and towards what is generally referred to as academic written language (e.g., Gibbons, 1999; Halliday, 1985). There are several ways that this development can be studied. That said, and to be clear, in written language, the use of more words or more complex syntactic structures such as subordinate clauses or relative clauses simply does not lead to enhanced communication or improved written fluency. Instead, in line with previous work in this area, we choose to examine changes in two specific markers of written fluency: LD and GI. Although we describe these terms later and provide representative examples for each one, for now, consider that LD helps us consider how complex a text is. A lexically diverse text contains a wide range of vocabulary and avoids repetitions through the use of synonyms. LD is typically calculated as the proportion of content words by the total words in a text (e.g., Halliday, 1985). GI, on the other hand, refers to the use of complex clauses such as subordinates in contrast to independent clauses. GI is employed to assess academic written language, which contains low condensed clauses thanks to the use of nominalizations and other strategies. GI is determined by calculating the total number of clauses as a proportion of the number of sentences in the text. Examining these two measures will allow us to understand how students transitioned their writing practices from an oral-like style to a more formal, academic register in the following manner: A high ratio of GI is representative of spoken language; whereas a low level of GI is a feature associated with academic written language. In terms of LD, oral language tends to be context-bound and flexible. That is, it uses fewer lexical items but more deictic expressions as well as a variety of communicative elements such as fragments or false starts. Written language, on the other hand, tends to include a large number of lexical or content items in each clause (e.g., Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018). Lastly, given that the acquisition of phonographic-alphabetic conventions of the written language is an essential part of the learning process, we also examine the development of accurate spelling as part of our analysis.

3. Literacy Development in SHL Writing

As stated earlier, a central and recurring question in SHL research over the last few years has been to identify whether and how SHL-specific instruction affects students’ biliteracy development. Previous work on this area has been largely concerned with what is generally referred to as academic writing. For example, Colombi (2002) analyzed the development of academic writing of two SHL learners enrolled in a Spanish composition course designed for learners referred to as native speakers. These learners used Spanish at home with their family and friends, but they had never received academic instruction in the HL. Although the course did not provide explicit instruction about register development or clause-combining strategies, it revolved around reading and writing academic essays. Colombi compared two expository/opinion essays written throughout the academic year, one written at the beginning of the academic course and another written nine months later. These two essays presented a summary of an author’s text and developed a thesis with supporting arguments. Her analysis focused on LD and GI (i.e., clause linking strategies), which, as we discussed before, are critical components of register differences. Her results showed growth in students’ LD and a decrease in GI. This was interpreted as a positive impact on the academic writing development of these students since a reduction of clausal structures indicates an ability to condense information, which as described earlier, suggests a transition from oral to a more academic-like register.

Relatedly, Elola and Mikulski (2016) conducted a study that focused on planning, execution, and revision, while applying fluency and accuracy measurements. They compared the writing processes of 12 SHL learners and 6 Spanish L2 learners. Interestingly, they were enrolled in a third-year Spanish grammar course originally designed for traditional Spanish L2 learners. Participants were first asked to watch 10-minute film footage followed by a series of warm-up questions. Later, they watched two excerpts from a movie and wrote two essays, in Spanish and English. The assignment was completed in class, with a 50-minute limit, and with access to an online dictionary. Fluency was calculated in two ways: (i) the number of words per T-unit, defined as a main clause and all the clauses depending on it, and (ii) the words per minute rate. Accuracy was evaluated by taking into account morphological, syntactic, lexical, and orthographic errors. Accent marks were excluded as they were not easily accessed on the computers; two measures were employed: (i) the percentage of error-free T units and (ii) the number and percentage of errors in specific categories such as gender and number agreement. While the results were not statistically significant for the fluency and accuracy measures, their analysis revealed that SHL learners were able to improve in accuracy when taking the time to revise their writings. That is, proofreading leads to the production of more accurate texts.

In a more recent study, Reznicek-Parrado et al. (2018) examined the written production of 7 SHL learners, who turned in two versions of two essays. The participants in this study identified as Mexican and were first- and second-generation immigrants enrolled in a Spanish program for Native Speakers. The two writing assignments were persuasive essays and were assigned during the fourth and seventh weeks of instruction. The second version of each essay was turned in after a tutoring session with a peer tutor, a student who had recently completed the HL program. Like Colombi (2002), Reznicek-Parrado and colleagues analyzed written production in terms of LD (the proportion of lexical items to the total number of words) and GI (i.e., clause linking strategies). Despite not reaching statistical significance levels, their results show a slight improvement in LD between Version 1 and 2 of Essay 2: An increase in the use of embedded clauses; a feature found in academic writing was observed across the four essays. Moreover, they found that peer tutoring positively impacted the literacy development of the students.

As a fundamental part of writing practices (and of literacy in general), the acquisition and development of accurate spelling stand as one of the most important goals for SHL themselves (e.g., Mikulski, 2006). Teaching spelling is usually a challenging task for several reasons, which include but are not limited to (i) the development of spelling is yet poorly understood, (ii) there is no guidance on the best teaching methodologies to address this issue, and (iii) traditional approaches to teach orthographic rules do not align with the latest teaching philosophies within the field. To date, there is a small number of studies that have examined this issue on bilinguals. Beaudrie (2012) presented a quantitative analysis of common misspellings in a corpus of SHL learners’ written production. The participants produced two untimed texts at the beginning of the semester, and these were later analyzed for inconsistent spelling such as syllable and word fragmentation errors and omission of accent marks. While her analysis revealed that SHL learners had a solid command of Spanish orthography, her findings also highlighted accent marks as the most frequent type of mistake in participants’ writings. More recently, Beaudrie (2017) conducted a study that focused on stress identification. Arranged in a pre and post-test design, participants received an introductory lesson and two explicit explanations of written accent rules with practice activities. Additionally, they also participated in three computer-based training sessions that provided listening exercises containing exaggerated and contrastive stress. The post-test results showed a positive improvement in students’ stress identification skills and ability to add written accent marks.

Along the lines of these studies, Llombart-Huesca (2017) chose to investigate the morphological awareness and spelling development of 41 heritage speakers. Different from these studies, however, these SHL learners were not receiving formal instruction in the HL. The participants completed a series of tasks such as a dictation task and a morphological analytical task. The results showed that attention to form is essential for the learner to notice orthographical patterns. Llombart-Huesca (2017) concluded that educators need to promote and foster language-analytical skills as a way of developing literacy in general, which could potentially promote restructuring effects short term. Considering the above, it seems like the development of spelling for SHL learners can be a long process and there is a need for educators to deviate from traditional approaches that can be tedious and develop alternative practices that keep students engaged in the learning process.

The combined evidence provided so far indicates that both, formal instruction, and peer tutoring benefit SHL learners with the development of their writing skills. Moreover, research has shown that instruction can also help with the development of accurate spelling.

While laudable and significant in their own right, when interpreting these findings, we ought to consider that the students that participated in these studies were allowed to either review their work and/or use outside sources when completing the tasks. In other words, we take those findings to indicate that the promotion of revision strategies, self-reflection, and self-assessment practices among SHL students in and out of the classroom with access to external resources will help them produce more accurate texts. That said, this raises an important question: Can the overall findings reported in previous studies be replicated when SHL learners are pressed with time and without the help of any outside sources? To attempt to answer this question, we designed and carried out a quasi-experimental written production study.

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

Forty-eight undergraduate students enrolled in classes within the Spanish HL program at a large public university participated in the study. Students were distributed into three classes, each one at a different level. The 2000-level class is described as a level for students with basic reading and writing skills. While students at this level lack formal exposure to Spanish, they have been exposed to the language in naturalistic settings. The 3000-level class is described as a course for students with some conversational and listening skills and is focused on helping students develop their reading skills and vocabulary as well as incorporating grammar and orthographic rules. Lastly, the 4000-level is designed for those students with some previous training in and regular use of Spanish. While instruction in the three levels follows a sociolinguistically informed and critical language awareness curriculum (e.g., Beaudrie & Loza, 2021; Leeman & Serafini, 2016; Pascual y Cabo & Prada, 2015) this class emphasizes discussions about the normative aspects of the written language, including the differences between formal and informal registers. All classes met 3 days a week, 50 minutes per session for a total of 16 weeks.

Following the best SHL teaching practices and philosophical positions described earlier, these classes exposed students to a variety of tasks and exercises that aim to assist and promote bicultural, bilingual, and biliteracy development (e.g., Beaudrie et al., 2014). While there is an emphasis on language and linguistic components, the principal focus lies on the SHL learners themselves, as legitimate speakers of the HL. Thus, instructors in the program are trained within current theoretical and pedagogical practices that (i) acknowledge students’ unique language variety and (ii) address students’ needs to enlarge their linguistic register and repertoire so they can successfully function in a range of social contexts, including most particularly the academy, professional, and public life scenarios.

First, HL learners completed the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP), a commonly used tool for assessing language dominance as well as an appropriate instrument to gather information about the participants’ background (Birdsong et al., 2012). The BLP is a self-report questionnaire that examines dominance via four modules: language history, language use, language proficiency, and language attitudes. The following table shows participants’ biographical information per course level and type of bilingualism. The self-rated proficiency measure was based on a 6-point scale, 1 being the lowest score and 6 being the highest score.

As can be seen, our participants, regardless of the course level they were attending, consistently exhibited higher ratings in English than in Spanish. This was not surprising as they were all considered to be English-dominant bilinguals. Within their Spanish ratings, they perceived their production skills (speaking and writing) to be lower than their perception skills (understanding and reading). As a whole, these findings are consistent with previous descriptions of perceived SHL proficiency (Beaudrie et al., 2014; Montrul, 2016).

4.2. Materials and Procedure

The data for this study come from a timed, pre- and post-semi-controlled written production experiment adapted from Polinsky’s (2014) study. Our SHL learners were asked to watch two[2] short video clips of one to two minutes each from the Russian cartoon Nu, pogodi! (“You just wait!”). Two main characters are shown in all videos: a mean wolf and a little bunny. In each video, the wolf tries to unsuccessfully catch the little bunny, who always ends up outsmarting the wolf.

The videos include a variety of actions in different scenarios. Importantly, no conversations or written language appeared in these videos, only music and other sound effects.

The main criteria for selecting the cartoons were based on the relative simplicity of the storyline as well as the range of vocabulary necessary to describe the events in each of the videos. As previous works had noted, adopting this type of narrative provides some advantages; first, presenting the plot of the cartoon as a cue ensured an objective comparison within and across subjects. Second, the relatively short length of each video did not place a burden on the participants’ short-term memory, which could have affected the results of the tasks. Lastly, since the participants were all familiar with the cartoon, it was easier to control the range of vocabulary used, especially in the case of HL learners at the lower end of the proficiency continuum, who often struggled with lexical retrieval. Importantly, students were asked to watch the same video clips at the beginning and the end of the semester; 14 weeks apart from each other.

Our participants were tested as a group in a language laboratory with their respective class instructors. After watching each video, they were asked to provide a detailed written description in Spanish of what they had just watched. Each video was only played once and they had four minutes to complete the task. Participants had access to a computer with commonly used writing and recording software. The same procedure utilizing the same materials was repeated at the beginning of the semester and after 14 weeks of instruction. Data from those participants who did not complete both the pre-and post-tasks or the BLP questionnaire were excluded.

4.3. Analysis

As stated earlier, the present study seeks to examine changes in SHL students’ beginning and end-of-semester written performances in terms of (1) LD, (2) GI, and (3) phonographic-alphabetic conventions of the written language.

LD is a measure used to determine the degree of “orality” in any given text. It explores the relationship between lexical and grammatical elements in discourse. The more lexically dense a text is, the more academic (and less oral) it is considered (e.g., Colombi, 2002; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018). It is traditionally determined by calculating the proportion of lexical carrying words compared to the total number of words in the text (e.g., Colombi, 2002; Michel, 2017). For our purposes, content-carrying words are nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs. For the sake of clarity, example (1) below illustrates how the data were analyzed. This sentence was taken from one of the written pieces of a participant’s essay. Bolded words represent lexical words and italicized words represent all function words.

(1) “Al principio del video puedes ver que el lobo come basura y encuentra un cigarro”. (9 lexical words / 15 total words = 0.6; percentage of lexical density 60%).

Example (1) contains a ratio of nine lexical words to a total count of fifteen words. Following the simple calculation stated above (i.e., lexical words divided by the total number of words) results in an LD value of 0.6 (or 60%).

Examining changes in students’ clause linking strategies, or GI, also allowed us to better understand how their writings transitioned from an oral-like style to a written-like style. GI is traditionally measured by counting the total number of clauses as a proportion of the number of sentences in the text. Considering this, and as pointed out in previous related work (e.g., Colombi, 2002; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018)., a high ratio of GI is representative of spoken language, whereas a low level is a feature of academic written language. For the sake of clarity, example (2) below illustrates how the data was coded and analyzed. This example was also taken from one of the written pieces of a participant’s essay. Each finite sentence was coded as either (i) a simple sentence, a combination of more than one (ii) coordinated and (iii) subordinated those clauses linked to the main one.

(2) “Luego, comienza a caminar por la pista y se apaga la cigarro, cuando el lobo mira al cielo, ve que fue el conejo”. (4 finite verbs of which 1 conforms a coordinated clause and 2 conform embedded clauses).

Example (2) shows a main, independent clause that contains a coordinated clause and two embedded clauses. Following the calculation stated above (i.e., dependent clauses divided by main clauses) results in a GI value of 3.

Lastly, to help us gain a greater sense of students’ overall development in terms of writing skills, we examined changes in the use of phonographic-alphabetic conventions of the written language. Consistent with previous studies that included this category as another accuracy measure (e.g., Elola & Mikulski, 2013, 2016), we coded and analyzed (the absence or presence of) accent marks, spelling, punctuation, and capitalization rules. As a whole, this measure allows us to understand the extent to which SHL students are able to develop insights about and gradually attain more control over these standardized conventions. For the sake of clarity, example (3) below illustrates how the data was coded and analyzed: three misspelled words (labo, cojio and espeso) and three missing accent marks in those same words.

(3) “Despues, el labo cojio su cigarillo y espeso a fumar”. (3 misspellings, 3 omissions of accent marks).

5.Results

Our presentation of the results is organized around the three markers of fluency described above, LD, GI, and the use of phonographic-alphabetic conventions of the written language. In that order, we present data from the beginning and end of the semester for each of the three classroom levels tested (i.e., 2000, 3000, and 4000).

Due to the relatively small and unequal sample sizes in our groups, we submitted our data to statistical analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test; a nonparametric test that allows comparison between two conditions without assuming that values are normally distributed (e.g., Eddington, 2016). Importantly, given that traditional statistical tests and p values have been argued not to be the best proxy for gauging practical significance in our field (e.g., Plonsky & Oswald, 2014), we decided to also conduct effect size analyses, which better characterize the meaningfulness of group differences (e.g., Cohen, 1992; Plonsky & Oswald, 2014). Following general guidelines, an effect size of .20 or lower is considered a small effect size, .50 is a moderate effect size and anything .80 or higher is considered a large effect size (Cohen, 1992; but see Plonsky & Oswald, 2014).

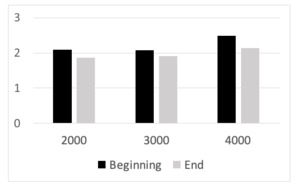

We start with LD, which, as described earlier, is a marker that gives insights into students’ literacy development. It has been traditionally defined as a measure of the proportion of lexical items (i.e., verbs, nouns, adjectives, and adverbs) and it is calculated as the proportion of lexical items to the total number of words Colombi, 2002; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018. Figure 1 below shows the beginning and end of the semester LD values for each of the three-course levels examined, which from left to right correspond to 2000, 3000, and 4000-level courses respectively. For the purpose of comparison, these values were converted into percentages. As can be seen, beginning and end of the semester LD values did not undergo any significant changes within or across groups. That is, as a whole, SHL instruction did not seem to affect LD development as it remained stable across levels over the course of the semester. This observation was supported by the lack of statistically significant differences with the Mann-Whitney test. At the 2000 level, the z-score was 0.07217 and p= .4721. At the 3000 level, the z-score was 1.15385 and p=.12507. At the 4000 level, the z-score is -1.34464 and p= .09012. Furthermore, Cohen’s d effect size was calculated for all three groups. These calculations yielded small-to-medium effect sizes for all of them, at 0.09, 0.33, and 0.22 respectively.

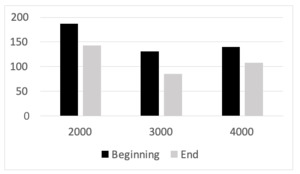

In addition to LD, we were also interested in examining the extent to which students’ use of English words was different from the beginning to the end of the semester. Figure 2 below shows a steady decrease in the use of English words for all three groups. Although the results of Mann-Whitney U test revealed no significant differences within each level (2000 level U= 80 (Z= 0.80408), p= .3120; 3000 level U= 74.5 (Z= 0.48718), p= .31207; 4000 level U= 144.5 (Z=1.036), p= .14917), Cohen’s d’ effect sizes indicated a moderate to large effect size for the 3000 (d = 0.46) and 4000 (d = 0.70) levels respectively. Combined, we take these findings to suggest that, as a whole, HL learners were using less English and more Spanish after 15 weeks of instruction.

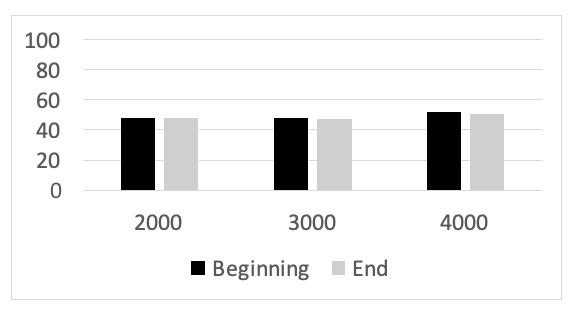

The second part of our analysis focused on GI. Recall that high GI values are considered to represent less academic writing style and, conversely, small GI values, are considered to represent more academic writing style (e.g., Colombi, 2002; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018). Considering this, and as can be seen in figure 3 below, our findings show that the students’ beginning of the semester production showed higher GI values across the three course levels compared to their production at the end of the semester. Although the developmental tendency is clear for all three levels, within group differences were analyzed with Mann-Whitney U test and did not reach statistical significance at p < .05 (2000 Z= -1.2578, p= .10383; 3000 Z= 1.02157, p= .15386; 4000 Z= -0.18983, p=.42465). The Cohen’s d calculation revealed moderate effect sizes for all group differences (2000, d= 0.34; 3000 d = 0.40; 4000 , d= 0.53).

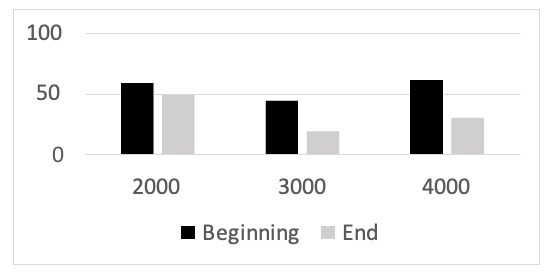

Lastly, the third part of our analysis focused on the students’ use of the orthographic/typological standardized conventions associated with the writing mode. Although admittedly there are a number of interesting aspects that could have been studied, herein we restrict our analysis to standardized spelling as well as omission and commission of accent marks. We chose these two since they simultaneously represent two of the biggest sought-after goals and challenges that HSs face in the SHL classroom. Importantly, as can be seen in figure 4 below, students’ use of standardized conventions of the written language seem to improve considerably over the course of a semester across the three levels.

Figure 5 below shows a comparison of the total number of errors made in spelling by group at the beginning and at the end of the semester. Visibly, the results seem to point in the direction of improvement over time. That said, the results of Mann-Whitney U test revealed no significant differences within each level (2000 level U= 76.5 (Z= 0.9649), p= .16853; 3000 level U= 63.5 (Z= 1.05128), p=. 14686; 4000 level U= 150 (Z= 1.33898., p=.09012). Calculation of Cohen’s d, however, indicated a moderate effect size for all levels (2000 Cohen’s d = 0.35; 3000 Cohen’s d = 0.59; 4000 Cohen’s d = 0.33).

Figure 6 shows the total number of accent mark errors (commission and omission) at the beginning and at the end of the semester. While there are no visible changes at the 3000-level class, there is a clear decrease at the other two levels, but particularly at the 4000 level. These results seem to point in the direction of improvement over time. This observation is supported statistically both from the results of the Mann-Whitney U test (U=105 (Z= 2.55623), p= .00523) and Cohen’s d large effect size (d = 0.87). At the 2000 level, although the results of Mann-Whitney U test revealed no significant differences (U= 71 (Z= 1.21761), p=.11123), Cohen’s d analysis revealed a moderate to large effect size (d= 0.55). At the 3000 level our analyses did not reveal a significant statistical difference (82.5 (Z= -0.07692), p=. 46812; d = 0.02).

6. Discussion

Although it is generally assumed that ascribing to current frameworks of SHL teaching and learning (e.g., Beaudrie et al., 2014) will yield positive outcomes regarding language and literacy development in our students, to our knowledge there is little available data to support this statement. The primary purpose of this study was therefore to fill this gap in the literature by examining students’ development over the course of a semester in the area of writing fluency as a component of general literacy. To this end, differently from a traditional intervention experiment in which learners receive specific instruction, practice, and feedback on a particular linguistic property before they are tested on it, in this study we investigated changes in our participants’ writings in the first draft of two essays: one at the beginning of the semester and one at the end. The data analysis focused on three specific aspects: (i) lexical density (LD), (ii) structural complexity and (iii) mechanical errors/written conventions. As a whole, our findings revealed group tendencies that point to positive gains on all three categories.

Regarding LD, our results showed that students did not produce a lexically richer text at the end of the semester, at least not to a degree of statistical significance. That said, their writing productions did show a slight tendency towards what would be considered more lexically developed productions. That is, the proportion of lexical items to the total number of words that the students produced increased modestly over the course of the semester. Our LD values were similar but, admittedly, less pronounced as those reported in previous studies (Colombi, 2002; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018). Since the educational contexts and the lived experiences of HSs in general are so vast, it is difficult to determine what may be the reason behind these findings, but perhaps the different nature of the classes themselves may be responsible for them. Interestingly, an examination of our students’ use of English words both at the beginning and at the end of the semester revealed moderate to large effect size difference between the two essays. That is, after four months of instruction students required less English to convey their messages.

In terms of GI, the results of this study indicate that our students’ writings changed over time in a favorable direction. In other words, there was a reduction of the clausal structures used, which we see as indicating an increased ability to condense information through stylistic and grammatical strategies such as the use of nominalizations. These findings, which are consistent with those reported in previous research (e.g., Colombi, 2002; Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018), are taken to indicate that students’ stylistic writings can become more academic and less oral as a result of SHL teaching.

As mentioned earlier, while the field of SHL has witnessed a considerable growth of studies with traditional pedagogical interventions concerned with the acquisition of specific grammatical structures, spelling acquisition and development has yet to be examined in detail. Beaudrie (2012, 2017) and Llombart-Huesca (2017) shed some light on this issue when they investigated the spelling and metalinguistic awareness in the writing of SHL learners. Beaudrie (2012, 2017) called for spelling interventions targeted to learners’ specific needs. Llombart-Huesca (2017) proposed including activities that promote morphological awareness in the curricula, an example could be teaching students how to divide morphologically complex words into their morphemes. With that in mind, the third and last part of our analysis focused on our students’ development of the orthographic standards associated with academic writing. Our findings revealed positive changes when comparing the mechanical errors produced at the beginning and at the end of the semester. As we see it, this is evidence of the positive impact that instruction can have on HSs’ language/literacy development: over the course of a semester students clearly become more aware of their language use and develop greater sensitivity to the importance of its mechanical details.

Combined, our findings seem to point to the potential nature (but not quite confirmed value) of SHL teaching approaches for the measures examined, at least not in a statistical manner. Although the lack of statistically significant results cannot and should not be overlooked, the general trends suggest development in a positive direction. Furthermore, we contend that the statistical uncertainty reported in our analyses may not be an accurate reflection of our students actual learning (or lack thereof), but rather an indicator that the task design may not have been the most appropriate for our purposes. First, recall that students only had 4 minutes to write each composition. As we see it, this short period of time does not really allow the students to produce language and edit it to the best of their abilities. Additionally, although the videos the students watched were very varied in terms of actions and plots, for the most part, the characters and content were very similar for all videos. This, we believe, forced our students to use the same content nouns (i.e., lobo and conejo) in all essays, which resulted in similar values at the beginning and end of the semester. Future studies should take these limitations into account and determine more optimal ways to collect data that may be more reflective of their actual skills.

7. Final Remarks

The premise of this study is that SHL instruction plays a decisive role in meeting the needs and desires of SHL learners. And while specific linguistic gains may be better understood as a direct result of explicit language instruction (Montrul & Bowles, 2010; Potowski et al., 2009), we contend that additional (epiphenomenal) benefits in this area may also be observed. Focusing on lexical density, structural complexity, and use of written conventions, our findings reveal a general but modest development at the group level. Although this sample is small and generalization is decidedly limited, the evidence suggests that (i) that SHL learners’ writing becomes more academic, (ii) that they use fewer English words, and (iii) that they make fewer mechanical errors. These findings suggest that the application of the general principles of Spanish HL instruction may not only result in positive academic outcomes such as the promotion of identity formation, the support of cross-cultural sensitivity, and the reinforcement of the capital that students bring to the classroom, as evidenced in previous studies but crucially, that they can also aid setting the foundations for improved linguistic outcomes.

Before concluding, we would like to posit a few ideas for future research. First, considering the abovementioned results for one semester of SHL instruction, we are left wondering the extent to which additional semesters of instruction could result in more substantial outcomes. In other words, could two semesters of instruction (for example) yield exponentially positive results? To find answers to this question, future studies should analyze the writing performance of HSs with 1, 2, or 3 semesters of instruction as an independent variable. Secondly, we wonder how our SHL learners’ results compare to those who took Spanish outside of the SHL program, that is, SHL learners that were students in mixed classes designed for traditional Spanish L2 learners. Lastly, the findings of our study, though moderate, seem to indicate that linguistically rich environments where meaningful and relevant interactions take place can benefit students’ writing performance and general literacy development.

Definitions of heritage speakers vary significantly depending on the perspective adopted. Broad definitions typically include individuals that have a cultural and affective connection to the HL, although they might not have communicative proficiency in the language. On the other hand, narrow definitions would only consider a HS as someone who can actually use the language (Polinsky & Kagan, 2007). In this study, we adopted Guadalupe Valdés’s (2000) definition: “a student who is raised in a home where a non-English language is spoken, who speaks or merely understands the heritage language, and who is to some degree bilingual in English and the heritage language”.

This study is part of a larger research project. Although participants watched a total of 5 videos, herein we focus on the written data from videos 3 and 4. Videos 1, 2, and 5, not analyzed in this study, elicited oral production.